The autocatalyst: A potted history

PGM recycling

10 May 2024

From humble beginnings...

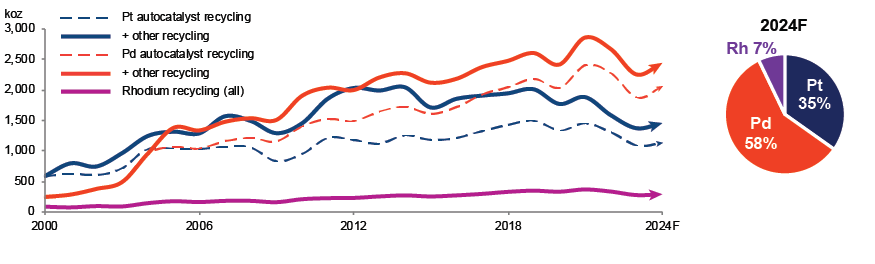

Platinum-group metals’ (PGMs) open-loop recycling is estimated to have grown from ~500 koz in the mid-1990s and less than 1 moz in 2000 to 4.21 moz forecast for 2024 in 3E PGM terms. From 2000 to 2019, PGM recycling grew by an average of 9% p.a., peaking at just below 5 moz just as the Coronavirus began to spread around the globe. Post-pandemic, and excluding an initial rebound in 2021, secondary volumes have struggled to maintain growth, as the chip crisis, rising interest rates and economic uncertainty prompted a shift in consumer behaviour in favour of holding on to vehicles for longer. Post-pandemic growth rates in recycled PGM volumes have averaged -5% p.a.; also not helped by a steep decline in PGM prices post-2022. Despite recent struggles in autocatalyst recycling, total secondary supply of PGMs is still comparable to the mined output of Russia and Zimbabwe combined.

PGM recycling: Global yield

Source: SFA (Oxford)

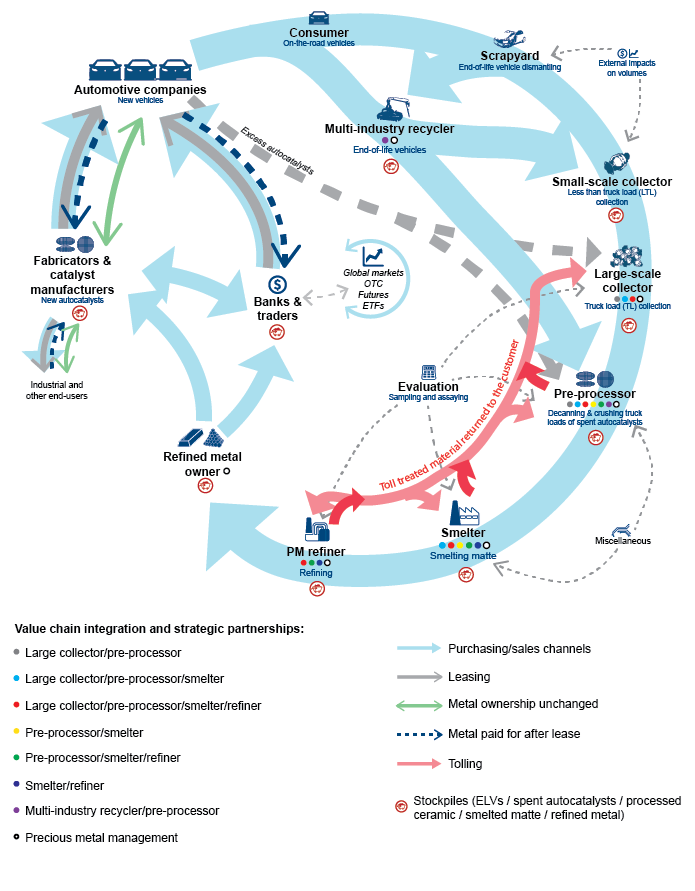

Complexity and scale of autocatalyst recycling

The recycling value chain is complex, crowded, opaque and multi-layered, with more than 10,000 first-line dismantler/ collectors (garage/scrapyard) per industrialised country, serviced by some 1,000 collectors feeding into around 100 global decanning/processing companies, which in turn provide recycled feed to smelters and refiners worldwide. Spent autocatalysts are traded on a global scale.

The big recyclers operate international collection operations. The contained PGM value is such that an individual catalyst’s material could criss-cross the globe as it passes from collector to collector to processor, smelter and refiner. Some processing companies will have sorting, decanning and processing plants in multiple global locations, which in turn collect catalysts from numerous surrounding countries. The USA dominates the global recycling of autocatalysts.

With the longest history of automotive emissions legislation (1970s) and PGM loadings on catalytic converters (1975), as well as the largest passenger car engines globally (2.9 litre average displacement), the country has the majority of autocatalyst recyclers. Therefore, a recycler can have a 10% share of the global recycling market, but only be based in the USA.

Global PGM recycling market structure

Source: SFA (Oxford)

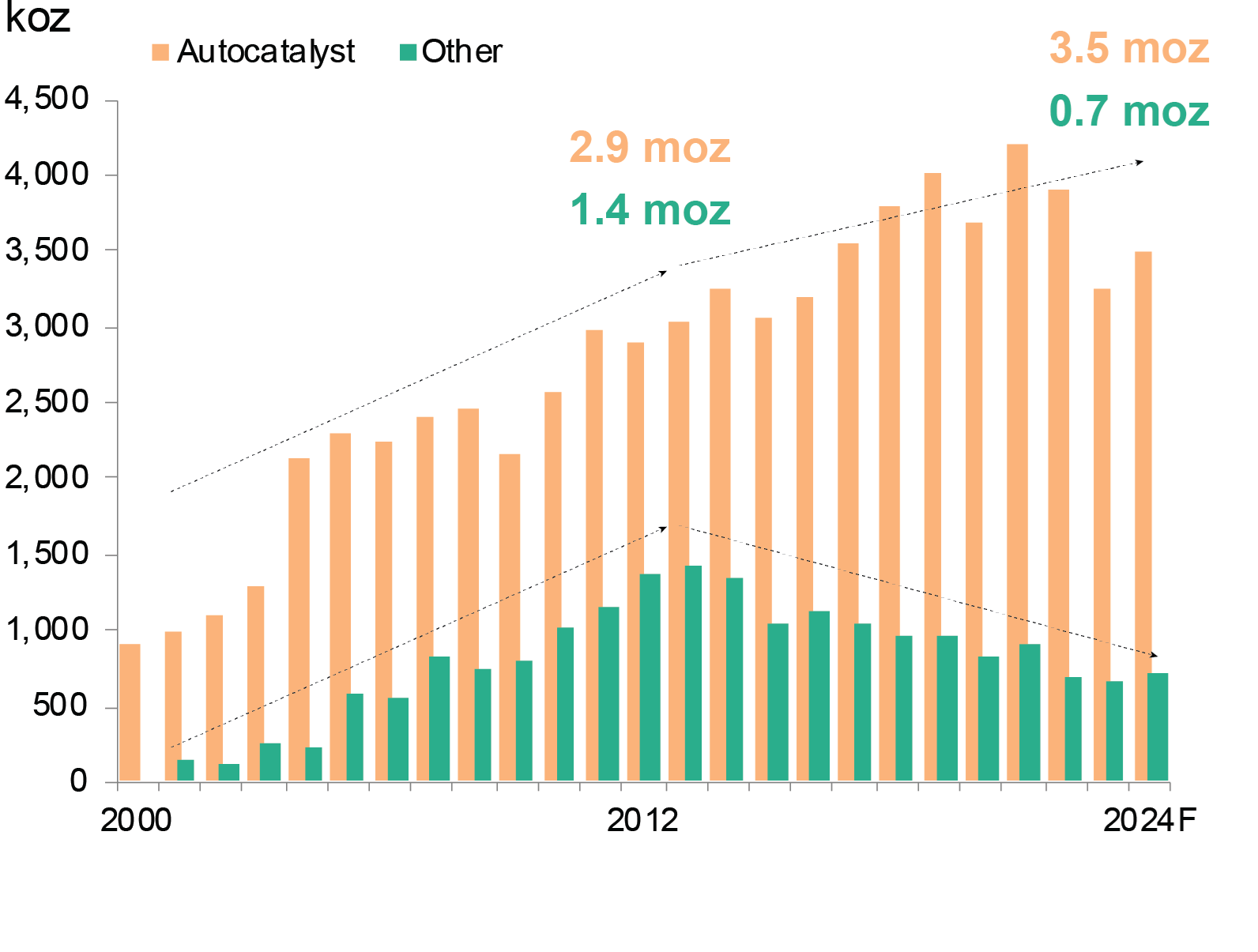

Non-autocatalyst PGM recycling

While the spent autocatalyst market is the largest component of PGM recycling, smaller volumes of secondary metals are yielded from the jewellery sector and waste electronics. Thanks to growth in the volume of metal yielded from spent autocatalysts, non-autocatalyst recycled PGMs are forecast to make up just 17% of total 3E PGM recycling in 2024. Looking back a decade, the proportion of non-autocatalyst recycling was almost twice as large. The peak and decline of non-autocatalyst recycled PGM volumes is largely related to the peak and decline of the platinum jewellery market in China. PGMs are also recovered from electrical and electronic waste (WEEE). Palladium is the more significant PGM recovered from WEEE owing to its long-standing use in multi-layer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs). However, with the increasing use of hard disk drives that contain a small quantity of platinum, the proportion of platinum recovered from WEEE has grown. Overall volumes from WEEE have declined, owing to thrifting and substitution over many years, as a

result of the rise and volatility in the palladium price.

PGM recycling volumes by source, 3E PGM

Source: SFA (Oxford)

PGMs need cars, cars need PGMs

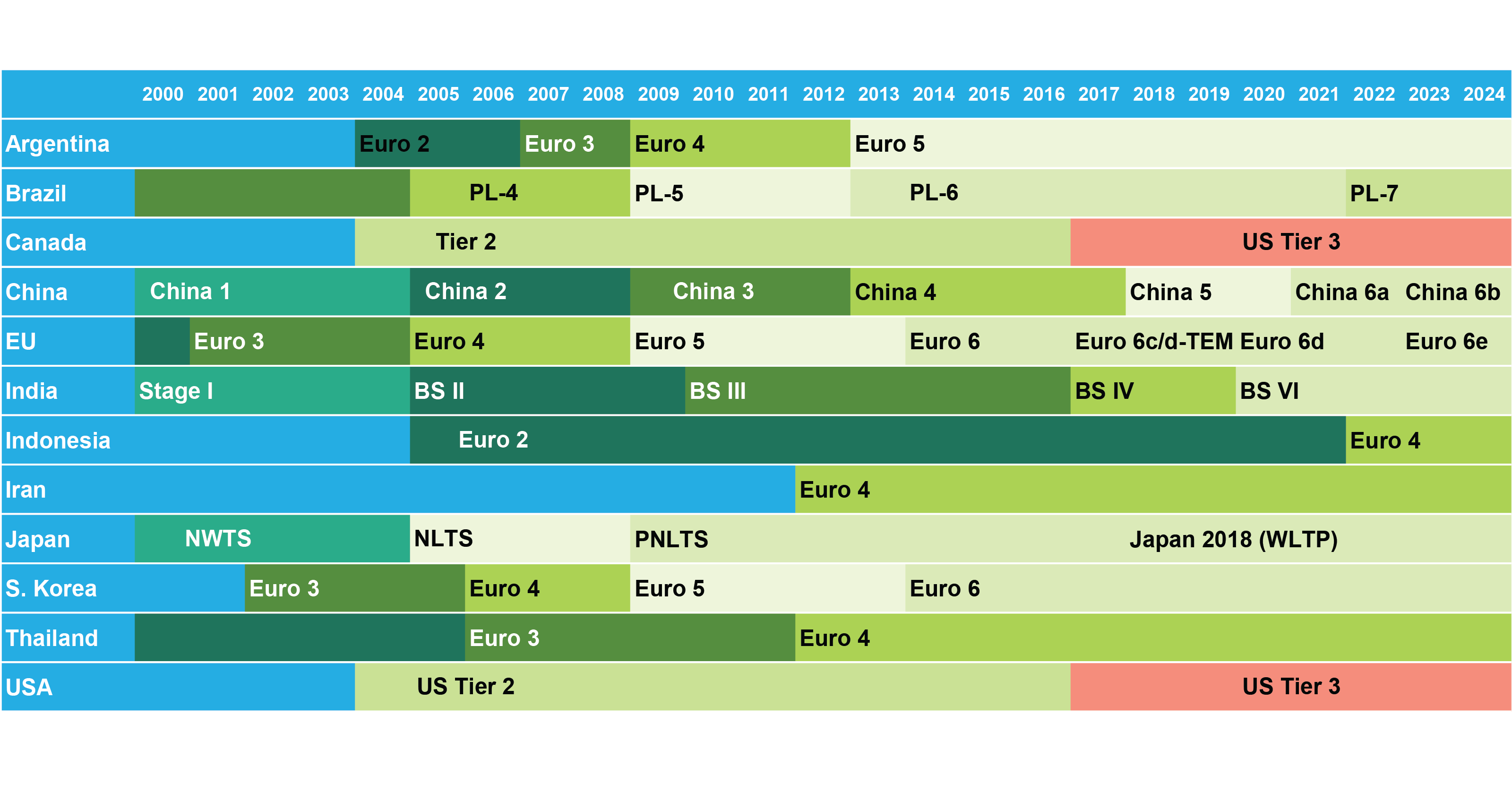

In a nutshell, PGMs are needed to clean up the wide range of gaseous and particulate emissions produced during the chemical and physical processes in internal combustion engines. As vehicle ownership grew, and with it air pollution, the world needed a way to clean up the air in urban areas, and PGMs were the answer. As a result, the automotive sector became the dominant force in raising PGM demand. In the decades since their first introduction, demand growth was assured through rising car sales, continued tightening of emissions legislation, spreading of emissions legislation to more and more countries, and increasing categories of combustion engines being included in emissions legislation, such as trucks, off-road machinery and 2- and 3-wheel motorbikes.

Spent autocatalysts

Source: SFA (Oxford)

Substitution away from PGMs’ use in autocatalyst aftertreatment is challenging as no other elements have comparable catalytic properties and durability in the hot exhaust environment. Platinum with rhodium in ‘twoway’ catalyst systems were used at first to control carbon monoxide (CO) and unburnt hydrocarbons (HCs). This was advanced in ‘three-way catalysts’ later which succeeded in the simultaneous oxidation of carbon monoxide and unburnt hydrocarbons plus the reduction of oxides of nitrogen (NOx ) in a single unit. Finally, as the popularity of diesel engines rose, and the damaging health impact of particulate matter emissions became clear, various diesel particulate filter technologies were introduced, some of which used some PGMs.

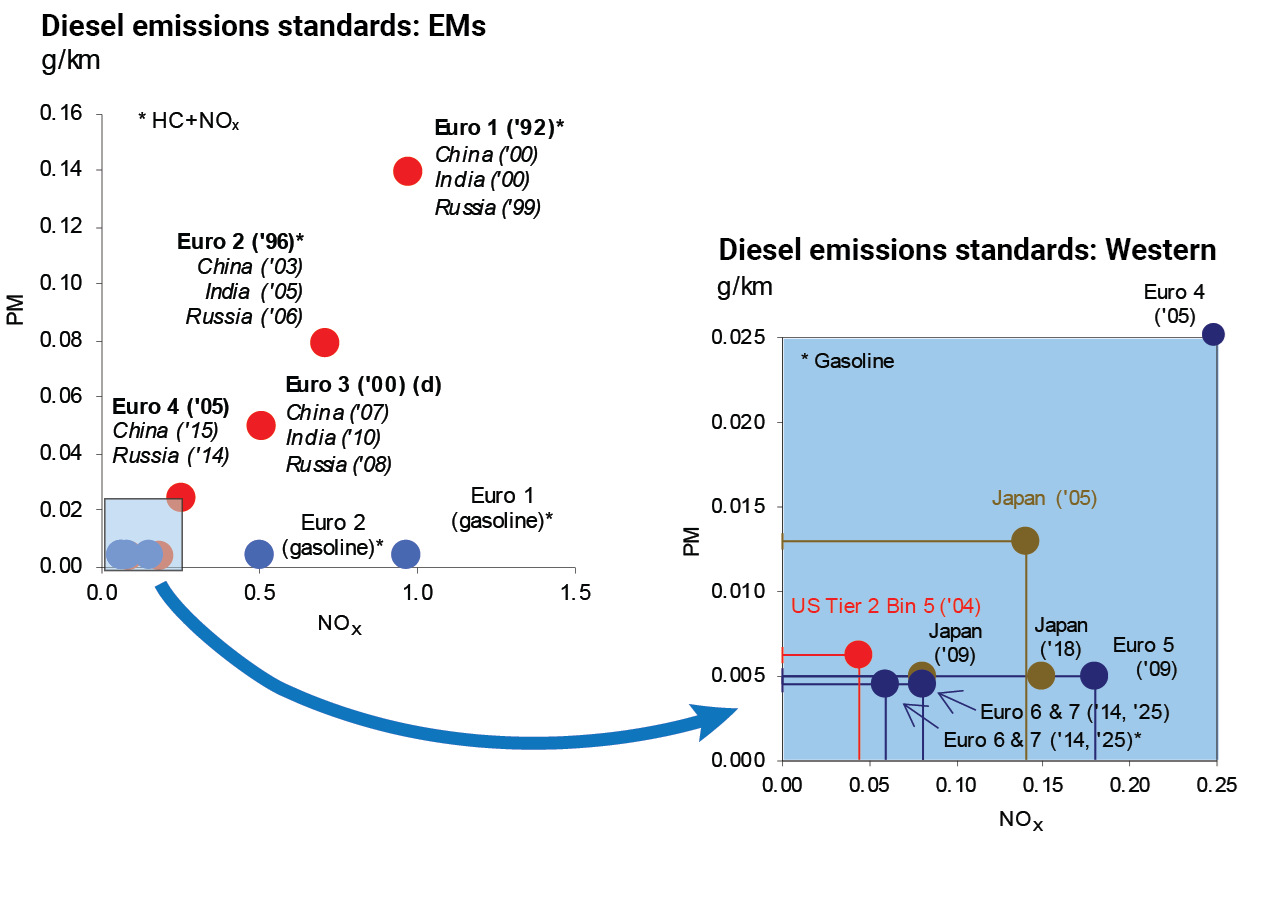

Palladium is more susceptible to sulphur poisoning than platinum, which meant that for dirtier diesel powertrains, platinum remained as the preferred catalyst. The introduction of Euro 4 legislation in 2005 cut the maximum acceptable sulphur content in diesel fuel to one-seventh of the previous limit, which meant some (at the time) lower cost palladium to be used in diesel car catalysts.

Palladium also helped to stabilise the catalyst at higher engine temperatures which also helped to boost demand. By 2015, palladium autocatalyst demand had reached a milestone of >10 moz.

Shifting PGM requirements in autocatalysts

Light-duty vehicle emissions legislation table

Source: SFA (Oxford), Transportpolicy.net

At the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s/early 1990s, the palladium price was hovering around $85/oz, and demand for palladium in the automotive sector totalled less than 250 koz, but over the next seven years demand would grow ten-fold. By 2001, demand in gasoline autocatalysts had reached 4.5 moz, and a combination of speculation, commercial panic buying and delays in Russian exports had pushed the price over $1,000/oz – a price that would not be seen again until 2017.

The price spike demonstrated the relative elasticity of demand as development shifted to the engineering-out of some palladium. In the years prior to 2001, autocatalysts were overloaded with PGMs as manufacturers substituted platinum with palladium at a near 2:1 ratio. As the price spiked, replacement was lowered to 1:1 palladium for platinum.

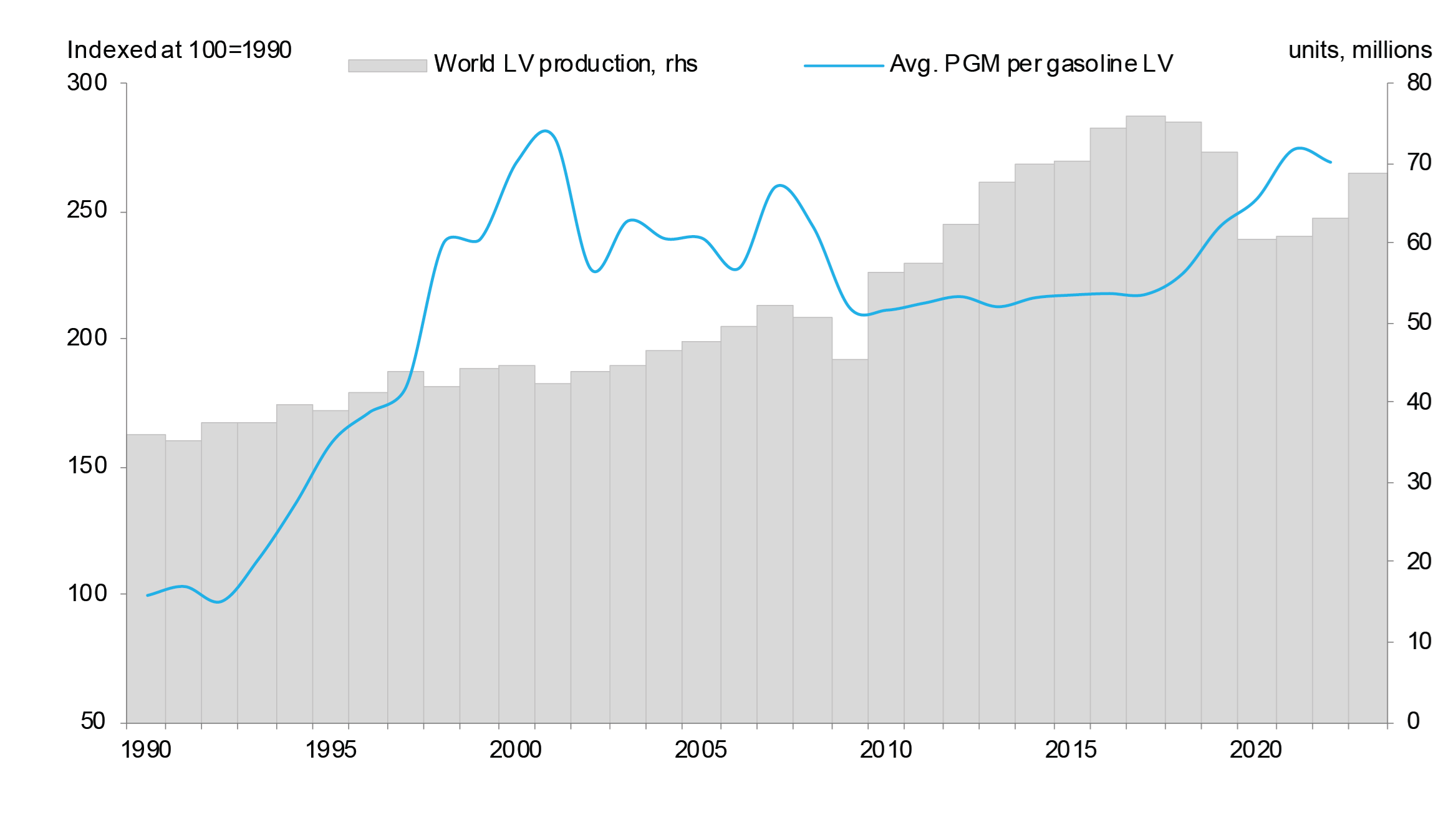

Annual global light-vehicle sales grew by nearly 100% from 1990 to 2017. At the peak in 2017, vehicle production reached 76 million units. With this growth came growth in PGM demand, particularly in palladium, as average global loadings in autocatalysts also rose by nearly nine times in response to increasingly stringent global emissions legislation.

There have been regional differences in emissions legislation over time. The USA has focused more on tougher NOx

limits, while the focus in Europe has been on particulate matter and, in the 2000s, cleaning up diesel powertrains. Generally, sequentially lower limits on tailpipe emissions have resulted in PGM loadings on autocatalysts outpacing the rate of thrifting, as shown in the chart overleaf.

Source: SFA (Oxford)

Rhodium is particularly effective at reducing NOx in engine emission gases, and therefore countries and regions that have emphasised the control of NOx have tended to have higher loadings. SFA’s data shows that gasoline light vehicles produced in Western Europe have seen the largest increase in average rhodium loadings since 1990.

Average loadings per gasoline light vehicle: Global

Source: SFA (Oxford), GlobalData

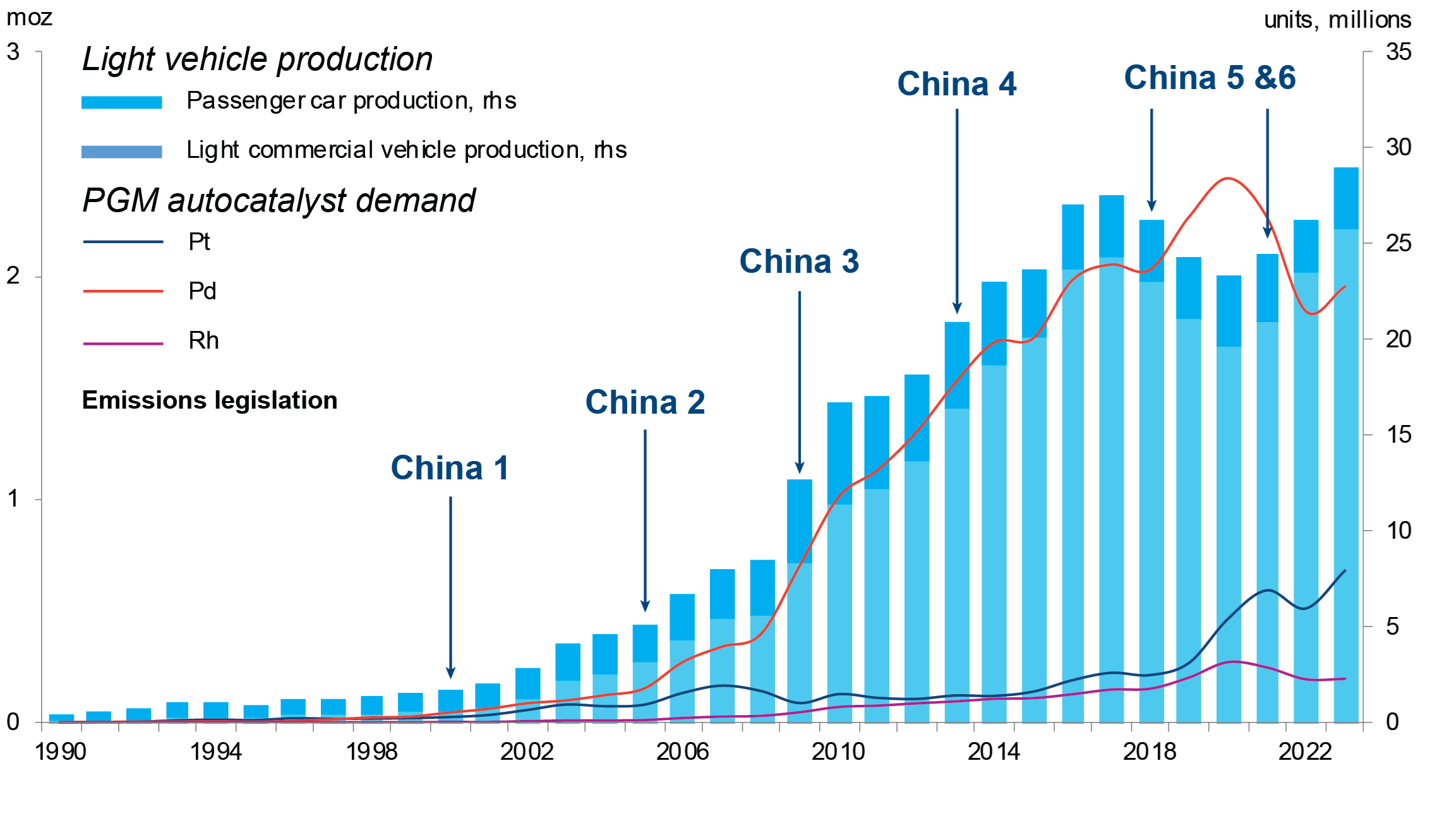

China’s economic boom in the 1990s and 2000s went hand-in-hand with an explosion in the nation’s demand for commodities, and PGMs were no exception. China first introduced tailpipe emission standards in 2000, which were based on Euro 1 standards. China could, however, progress its standards much more rapidly, as car manufacturers could apply ‘off the shelf’ technology developed elsewhere in the preceding decades. Cumulative automotive palladium demand from 2005- 2015 totalled only 504 koz in the Chinese market.

However, in the following decade, cumulative demand multiplied to 8,500 koz as vehicle production capacity rapidly expanded to satisfy demand from the growing middle class, and emission standards tightened.

In the last few years, record-high palladium prices prompted autocatalyst manufacturers and automotive OEMs to initiate substitution of palladium for platinum in gasoline three-way autocatalysts. This has been concentrated in the US and Chinese markets. However, higher total average loadings, particularly in China, have gone some way to offset this trend. Ultimately though, the metal used in today’s catalysts will take at least a decade to enter the pool of recovered secondary metal.

China's autocatalyst expansion

Source: SFA (Oxford), GlobalData

Autocatalyst demand growth has been huge as China and other emerging markets have begun to align emissions legislations with those in the EU and US. The way to make this expansion sustainable and cost-effective is through the use of recycled PGMs in these new autocatalyst markets, and across the globe.

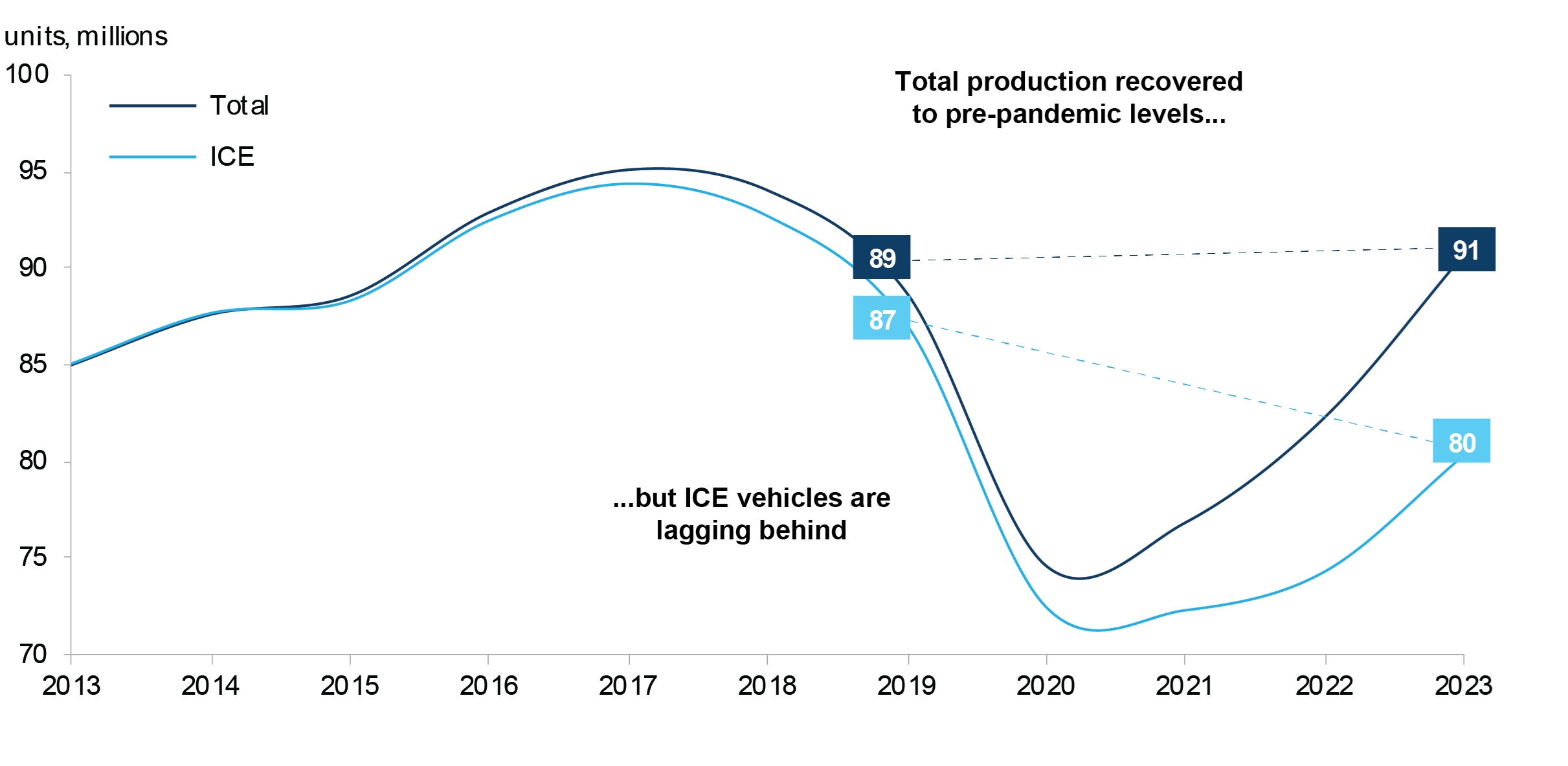

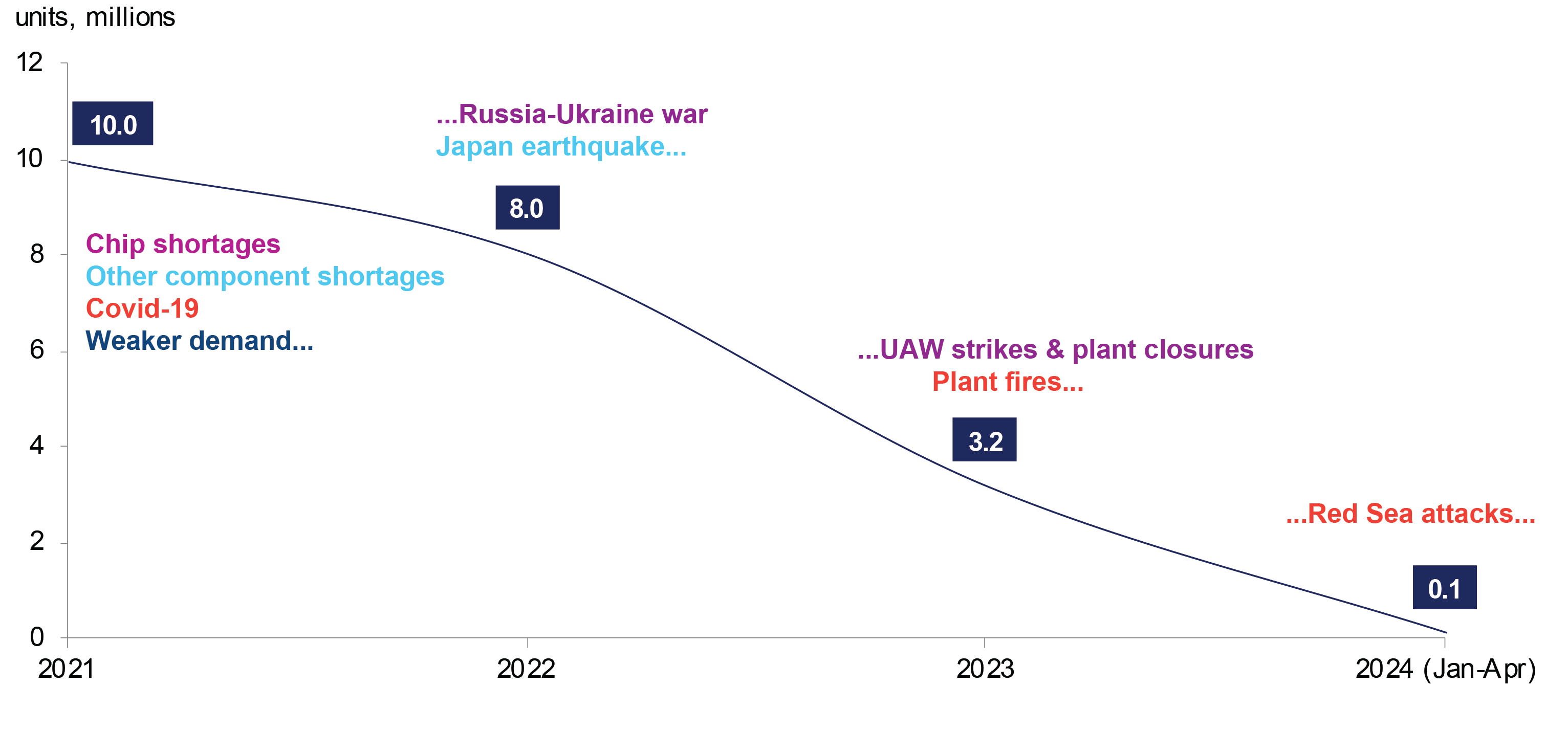

The rapid shift in automotive production is slowly unwinding

The impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the global automotive industry were seismic in terms of both the ability to produce vehicles and consumer behaviour. The drop in demand for new vehicles in 2020-2021 was compounded by the semiconductor chip crisis – an effect of the shift in consumer preferences towards hand-held electronics and PCs in the early stages of the pandemic, disrupted global supply chains, and China’s late and strict Covid lockdowns. Global light-vehicle production dropped by 10 million units year-on-year in 2021, and although most supply chain disruptions have now been worked out of the system, internal combustion light-vehicle production numbers have yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. As BEV sales also rose rapidly in the recovery period, combustion engine vehicle sales are unlikely to match the pre-Covid peak again.

Global light-vehicle production

Source: SFA (Oxford), GlobalData

The combination of limited driving of cars during Covid lockdowns, the shortage of new vehicles, the rise in second-hand car values as a result, and increasing interest rates affecting disposable incomes seems to have led to cars staying on the roads for longer, effectively starving scrapyards of old, end-of-life cars, and the autocatalysts that come with them.

Disruptions to light-vehicle production

Source: SFA (Oxford), GlobalData

Autocatalyst recycling volumes have suffered a decline as a result in recent times. However, the return of growth is highly likely, as vehicles age and reach the end of their lives, and more of those vehicles will have higher PGM loadings on their autocatalysts. Some of this scrapping will be boosted through government policy, with both ‘carrot' and 'stick’ being applied: China, for example, has just announced a subsidy scheme, encouraging owners of older, more polluting cars to scrap them and replace them with a new model. An increasing number of European countries are imposing no-go zones or higher parking fees for older polluting cars in their bigger cities.

In SFA’s view, the question of the growth in recycling volumes is therefore a longer-term certainty, while the timing of near-term directional momentum still has several question marks hanging over it.

A post-Covid assessment of the PGM autocatalyst recycling market

For more details on our latest ground-breaking 200-page PGM Autocatalyst Recycling Market Study, an essential resource for understanding the current landscape and prospects of the industry, click the link below:

Brought to you by

Daniel Croft

Commodity Analyst

How can we help you?

SFA (Oxford) provides bespoke, independent intelligence on the strategic metal markets, specifically tailored to your needs. To find out more about what we can offer you, please contact us.