Pakistan’s REE partnership advances US goals

Critical minerals, policy, and the energy transition

15 October 2025

Pakistan’s rare earths partnership advances US supply chain security and independence

Historic breakthrough and strategic imperative

The first shipment of rare earth elements and critical minerals from Pakistan to U.S. Strategic Metals (USSM) in Missouri, marks a symbolic breakthrough for both governments and a historic first for Pakistan’s mineral sector. For Washington, it represents a timely boost for its defence, clean energy, electric vehicle, aerospace, advanced manufacturing, and electronics supply chains, and an urgent effort to secure critical materials beyond China’s reach as competition over global supply chains intensifies. For Pakistan, it offers a narrow window to prove it can translate mineral potential into credible industrial capacity before attention and investment drift elsewhere. However, deep structural, financial and security challenges between the two nations will determine whether the initiative evolves into a functioning industrial partnership or fades into symbolism, an outcome Washington can ill afford.

Pakistan formally entered the global critical minerals trade on 2 October 2025, sending its first consignment of enriched rare earth elements and critical minerals to USSM under a $500 million agreement. The shipment, containing antimony, copper concentrate and rare earths including neodymium and praseodymium, marks the start of a partnership between USSM and Pakistan’s Frontier Works Organisation (FWO). Signed in September, the agreement sets out plans to build an integrated value chain from exploration and processing to refining within Pakistan. The delivery is historic, but turning an announcement into a sustainable industry will be far more demanding. This partnership serves important strategic signalling purposes and provides crisis insurance for US supply chains. However, expecting it to meaningfully reshape global critical minerals markets or deliver transformational economic benefits to Pakistan soon is unrealistic. In practical terms, the delivery timeline should be viewed in phases: a strategic demonstration period of roughly two to three years, modest commercial scaling over five to seven years, and the potential for meaningful impact only after a decade, assuming security, technical, and financial challenges are successfully managed.

Financing uncertainties and policy gaps

The financing and legal structure of the partnership remain unclear. Neither side has specified whether the investment is equity-based, debt-financed, or structured as a public–private arrangement or whether institutions such as the US Development Finance Corporation, EXIM Bank, or Pakistan’s sovereign funds are providing guarantees. Nor has it been confirmed whether the September MoU has evolved into a binding commercial contract. Without clarity, it is difficult to know whether the deal represents an executable industrial venture or primarily a strategic demonstration.

Pakistan’s ambitions depend on a coherent domestic policy. The government frequently cites $6 trillion in untapped mineral wealth, yet mining contributes only 2–3% to GDP and 0.1% to global exports. The $6–8 trillion figure is speculative and lacks technical credibility, reflecting a theoretical in-ground valuation of unverified mineral occurrences rather than proven, economically recoverable reserves. Pakistan has no JORC or NI 43-101-compliant resource data, and the figures conflate geological potential with commercial feasibility. Reko Diq contains proven and probable reserves (Cu, Au, Ag, Mo, Co and trace REEs – Ce, La, Nd, Pr) worth about $60–74 billion, while much of the country remains under-explored and poorly mapped for critical minerals. Genuine potential exists in Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit-Baltistan, but realistic valuations place total recoverable wealth at $100–300 billion over several decades. The trillion-dollar narrative persists primarily for political and promotional reasons, obscuring the need for credible geological surveys, institutional reform and modern exploration to establish verifiable, economically viable reserves.

Pakistan still lacks a comprehensive critical minerals strategy, and the regulatory environment remains fragmented. Aligning the emerging U.S. partnership with Chinese-backed projects under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) will require delicate political balance, particularly in Balochistan, where foreign interests have long dominated large-scale mining. The Reko Diq copper and gold project, jointly operated by Barrick Gold and the Government of Balochistan, is being revived after years of legal disputes and represents one of the world’s largest undeveloped copper and gold deposits, with estimated resources exceeding 40 million tonnes of copper and 50 Moz of gold. Saindak, by contrast, is an older, fully operational project run by the Metallurgical Corporation of China under a long-term lease, producing around 20,000 tonnes of copper, 1.5 tonnes of gold and 2.5 tonnes of silver each year. Both projects illustrate the tension between attracting foreign capital and retaining national control over mineral revenues. Integrating the new U.S. partnership into this landscape will test Islamabad’s ability to manage competing strategic and economic interests without alienating Chinese investors or reigniting provincial grievances. Establishing Special Economic Zones or offering tax incentives for downstream processing could help attract investment and technology transfer, but no such measures have yet been implemented.

Geological potential

Pakistan’s geological potential is genuine but limited in scale compared with established producers. Rare earth deposits are distributed across Balochistan (Ce, La, Nd, Th, U), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Ce, Nd, Pr, Sm) and the northern areas (Ce, Nd, Y, Dy), with the Chagai, Swat–Dir and Makran coastal regions offering the most promising prospects. In Balochistan, granitic and pegmatite formations in the Chagai district are associated with carbonatite complexes containing light rare earth elements such as cerium (Ce), lanthanum (La) and neodymium (Nd), together with trace amounts of thorium (Th) and uranium (U). The Swat–Dir belt in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa shows geological characteristics similar to the Himalayan rare earth-bearing zones of northern India and has confirmed REE concentrations consistent with small carbonatite systems across South Asia. The Makran coastal region also hosts monazite-bearing heavy mineral sands rich in cerium (Ce), lanthanum (La) and neodymium (Nd), extending for roughly 200 km along the Arabian Sea and geologically comparable to coastal placer deposits mined in India and Sri Lanka. Fly ash from the Thar coalfield (Ce, Nd, Y) has been identified as a low-grade unconventional feedstock, with concentrations comparable to coal-derived REE recovery projects currently under assessment in the United States and China.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Swat–Dir belt (Ce, Nd, Pr, Sm) shows geological similarities to the Himalayan rare earth-bearing zones of northern India. Detailed sampling from the Sillai Patti carbonatite (Ce, La, Nd) records neodymium (Nd) at around 314 ppm, cerium (Ce) at 915 ppm and lanthanum (La) at 519 ppm, giving total rare earth contents between 1,900 and 3,300 ppm, with localised pegmatites near Skardu and Chilas (Ce, Nd, Y) reaching up to 10% REE oxide. These findings confirm Pakistan’s potential for small, high-grade deposits suitable for pilot extraction.

Along the Makran coast, heavy mineral sands extending for nearly 200 km along the Arabian Sea contain monazite (Ce, La, Nd, Th) averaging 1–2% REE oxide equivalent. These coastal deposits, rich in cerium (Ce), lanthanum (La) and neodymium (Nd), are geologically comparable to monazite placer systems currently exploited in India and Sri Lanka. In addition, fly ash from the Thar coalfield (Ce, Nd, Y, La) contains 200–400 ppm of total REEs, primarily lanthanum (La) and cerium (Ce), and is being assessed as a potential unconventional feedstock for recovery through secondary processes.

Pakistan’s total recoverable rare earth oxide potential is estimated at between 100,000 and 500,000 tonnes, enough to make it a potential Tier-2 source alongside Vietnam or Myanmar, but far below major producers such as China, Australia, Brazil and India. More than 95% of the country’s mineral terrain remains underexplored, and no internationally certified reserve estimates have been published. Converting geological promise into economic value will depend on systematic exploration, metallurgical testing and investment in infrastructure, particularly in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where logistics and security remain persistent constraints.

Estimates of 100–500 kt of total rare earth oxides are geologically significant but modest compared with Myanmar, Australia and China. Myanmar’s ionic clay deposits exceed one million tonnes, Australia’s Mount Weld project has reserves greater than four million tonnes, and China’s Bayan Obo complex holds more than 40 million tonnes. Pakistan’s deposits, though diverse, are smaller, scattered and underexplored, reflecting decades of limited investment in systematic geological surveys. The main constraint lies in the absence of midstream capability. Pakistan can extract and concentrate ore but lacks the infrastructure and expertise for chemical separation, solvent extraction and oxide-to-metal conversion. These processes are capital-intensive and environmentally sensitive, requiring stable power, reliable water supply and specialised reagents.

Processing constraints

US Strategic Metals’ proprietary hydrometallurgical process could help bridge part of this gap by enabling selective recovery of critical elements through aqueous leaching and precipitation. However, the scalability of this technology remains untested in Pakistan’s geological context, and the company would need to adapt it to varying ore chemistries and local operating conditions. In addition, licensing restrictions on advanced metallurgical equipment, coupled with the high energy and water demands of refining in Balochistan’s arid terrain, present further obstacles. Without dependable energy infrastructure and environmental safeguards, commercial-scale rare earth refining in Pakistan is unlikely in the near term. Antimony offers a more immediate opportunity for Pakistan’s emerging mineral sector. Discovered in central Balochistan earlier this year, it is used in ammunition, flame retardants, semiconductors, batteries and solar technologies. The United States imports all of its antimony, while China controls roughly half of global production and more than 60% of processing capacity. This supply concentration and Beijing’s recent export restrictions have pushed prices above $50,000/tonne and elevated antimony into a strategically sensitive category. The metal’s appeal lies not only in its price or military relevance but in its practicability. Unlike rare earth elements, antimony can be mined and processed using existing metallurgical infrastructure with relatively modest capital. Extraction and flotation techniques are simpler than the complex chemical separation required for REEs, and pilot-scale production is achievable in a few years rather than a decade.

Key mineral opportunities

Antimony diversification for Washington addresses a glaring supply-chain vulnerability. In 2025, President Trump issued an executive order restoring “Department of War” as a secondary, preferred title for the Department of Defense, and antimony has been identified among the materials of defence concern in U.S. critical and strategic minerals policy. (Note: “Department of Defense” remains the legal name.) The metal is integral to ammunition primers, flame-retardant compounds and other advanced electronics. For Pakistan, antimony represents a credible near-term export opportunity and a path to earn strategic credibility while REE development proceeds. The OGDCL–PMDC joint venture aims to move swiftly from exploration to pilot production, aided by FWO’s infrastructure capabilities and adjacency to copper operations. Still, success hinges on regulatory consistency, accountable governance and on-the-ground security.

Copper remains one of the most indispensable materials in modern defence production, ranking as the second most consumed metal by the Department of War. It underpins almost every element of the military industrial base, from power systems and communications to weapons platforms and infrastructure. Copper’s exceptional electrical conductivity makes it vital to military energy networks, powering everything from base generation units to field-level distribution systems. Modern command and communication structures rely on copper for secure satellite links, encrypted data transfer and real-time battlefield coordination, where reliability is paramount. It is also critical in military platforms, including aircraft, ground vehicles, ships, submarines, missiles and ammunition. Advanced systems such as guided missiles and drones depend heavily on copper wiring and components. Ammunition production alone illustrates the scale of demand: the Department of War plans to expand annual production of copper-containing 155mm shells from 93,000 to 1.2 million by 2025 to meet operational requirements. Military bases depend on copper for power distribution, lighting, heating and cooling networks. At the same time, radar systems and electronic warfare equipment use it for high-conductivity connections capable of withstanding extreme environmental and operational stress. In short, copper forms the electrical and structural backbone of U.S. defence capability, and any disruption to its supply or processing capacity carries direct strategic consequences. Yet U.S. copper mining now accounts for just 5% of global production, and refining capacity has fallen to 3.3%, while China controls over half of global smelting. Pakistan’s copper concentrates, though limited in scale, provide incremental diversification when Washington imposed 50% tariffs on derivative imports under Section 232 and launched a national security investigation into copper supply vulnerabilities.

Neodymium and praseodymium, the rare earths included in the first shipment, are crucial for high-performance magnets used in a range of advanced defence technologies. These include fighter jets, naval propulsion, missile guidance, radar systems, drones, submarines, satellite communications, electronic warfare equipment, unmanned vehicles, precision-guided munitions, advanced surveillance technologies, laser targeting systems, space-based sensors, and next-generation defence platforms such as the F-35 Lightning II, B-21 Raider stealth bomber, Zumwalt-class destroyers, Virginia-class submarines, and hypersonic missile systems. Pakistan’s capacity to supply even limited quantities of these critical elements establishes a strategic foothold and contingency reserve, offering allies a vital alternative supply line beyond Beijing’s sphere of control.

Security risks and geopolitical tensions

Security and institutional weakness remain Pakistan's most significant risks to sustained mineral development. The Baloch Liberation Army and other separatist groups have repeatedly targeted mining and infrastructure projects, seeing them as exploitative or exclusionary. Since 2018, more than 50 attacks have been recorded. Security costs reflect these challenges but are often overstated. Government data show that total spending on security at the Reko Diq site reached roughly Rs 3.74 billion (about $13–14 million) by mid-2025, covering the deployment of around 700 personnel from the Frontier Corps under a dedicated Security Services Framework Agreement. It highlights the high cost of operating in Balochistan’s volatile environment. Mines can be defended, but road links, power transmission lines and water pipelines remain exposed, increasing risk premiums and insurance costs for the whole sector.

Overlapping federal and provincial jurisdictions also hamper mining governance, inconsistent legislation and slow regulatory approvals, which add further uncertainty for investors. The Balochistan Mines and Minerals Act 2025, which requires state participation in large projects, may discourage private investment. FWO’s military management brings operational discipline but questions civilian oversight and transparency. Pakistan’s record of opaque contracts, most notably the Reko Diq arbitration case, underlines the need for independent audits, public royalty reporting and predictable legal protections for investors.

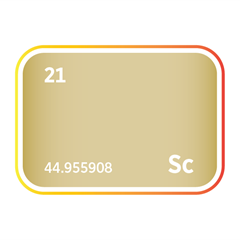

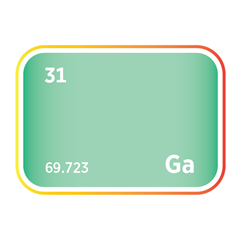

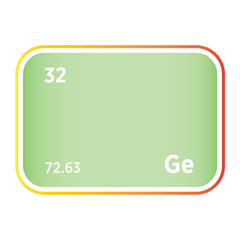

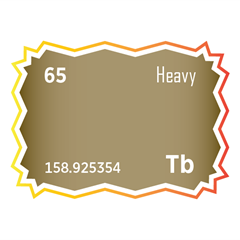

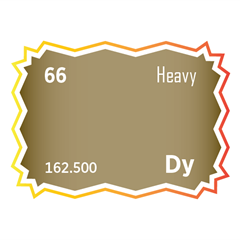

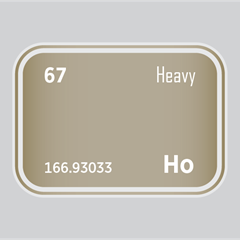

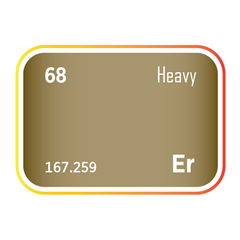

The move comes at a sensitive geopolitical moment. In April 2025, China imposed export restrictions on seven medium to heavy rare earth elements (Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Lu, Sc, Y), targeting materials essential for high-performance magnets, defence technologies and clean-energy applications. In October 2025, Beijing expanded the controls to include five additional rare earths (Ho, Er, Tm, Eu, Yb) and extended the measures to cover processing and separation equipment. Earlier, in December 2024, China had already banned exports of antimony, along with gallium and germanium, to the United States, signalling its intent to use critical minerals as strategic policy instruments. Together, these steps highlight Beijing’s determination to preserve its dominance in advanced-material supply chains and to maintain leverage over industries dependent on critical technologies. Pakistan must balance its deep economic ties to Beijing through CPEC with a new strategic opening to Washington. India, pursuing its own critical minerals partnerships with Australia and the United States, will watch developments closely. For Washington, the deal supports the broader Indo-Pacific goal of diversifying supply chains, even if Pakistan’s contribution remains limited.

Phased roadmap and systemic barriers

The recent $500 million partnership between Pakistan’s Frontier Works Organization (FWO) and US Strategic Metals (USSM) represents a promising start, but multiple systemic constraints will prevent rapid scaling. The Pakistan–US partnership follows a three-phase development plan to build capacity gradually.

-

Phase 1 (2025–2026) focuses on exporting readily available minerals, including antimony, copper concentrates, and basic rare earth ores, to generate early revenue.

-

Phase 2 (2026–2028) involves establishing domestic processing plants and refineries, incorporating technology transfer for rare earth element (REE) separation and purification.

-

Phase 3 (2028 and beyond) aims for large-scale exploration and mining, targeting five to ten high-potential REE projects across Pakistan.

The first shipment in October 2025, which included antimony, copper concentrate, and rare earth elements such as neodymium and praseodymium, marked a symbolic milestone. However, it represented only sample quantities rather than commercial-scale exports, highlighting the long journey ahead.

The most pressing challenge is the processing infrastructure deficit. Pakistan currently lacks the industrial-scale metallurgical and refining capacity necessary to process rare earths domestically. Only laboratory-scale facilities exist at the Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR) and the Atomic Energy Minerals Center (AEMC). There is no integrated pilot plant capable of continuous beneficiation or hydrometallurgical testing of REE ores. As a result, Pakistan remains dependent on foreign toll-processing, primarily in China and Malaysia, which inflates costs and undermines strategic autonomy.

The second major obstacle involves security and operational challenges. Pakistan’s mineral-rich regions remain vulnerable to instability and insurgent activity, particularly in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). Balochistan, which contains around 80 per cent of the country’s mineral wealth, experiences recurrent militant attacks on mining and infrastructure projects. The Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) has targeted foreign workers, logistics convoys, and extraction sites, deterring foreign investment and disrupting operations. Additionally, illegal mining continues to drain national revenue, costing an estimated $500 million annually.

A third key constraint arises from infrastructure and logistics bottlenecks. Poor transport networks, unreliable energy supplies, and severe water scarcity continue to impede large-scale development. Transport inefficiencies are significant, with the cost of moving concentrate from Swat to Gwadar, a journey of 1,800 km, reaching around $120/tonne, roughly double the rate of comparable Australian routes. Intermittent power supply in Balochistan and KPK increases operational expenditure by 15-20%, while the region’s arid climate, with annual rainfall below 200 millimetres, severely limits the availability of water required for mineral processing.

Environmental and social risks compound these challenges. Mining in water-scarce and ecologically fragile areas threatens ecosystems and local communities. Without visible local benefits, resentment is likely to grow. Partnerships with institutions such as NUST, UET, and Missouri S&T could build domestic expertise, while clear commitments on employment, training, and community investment would help secure local acceptance.

Taken together, the materials in Pakistan’s shipment, antimony (Sb), copper (Cu), neodymium (Nd), and praseodymium (Pr), address three of the Pentagon’s most pressing vulnerabilities, total import dependence on antimony, inadequate defence-grade copper processing, and near-total reliance on Chinese rare earth refining. For Washington, the value of Pakistan’s cooperation lies not in scale but in access and resilience. In an era of strategic competition and supply chain weaponisation, any non-Chinese source, however modest, provides a vital hedge against disruption.

The first delivery demonstrates that Pakistan can supply critical minerals to international markets and, crucially, to the United States. The challenge now is not symbolic delivery but sustained performance, scaling output reliably, maintaining standards, and meeting schedules. In the short term, progress will likely come from copper and antimony exports and pilot-scale processing. Medium-term gains depend on developing basic refining capacity and a predictable regulatory framework, while long-term success requires stable governance, improved infrastructure, and continued US engagement. For Washington, the priority is supply security rather than sustainability, and every credible alternative to Chinese processing capacity strengthens its position within the global critical minerals chain.

Historic lessons

The situation is more complex for Pakistan, and further work lies ahead. If Islamabad can consolidate this partnership through transparency, technical competence, and political stability, it could modestly reshape the regional critical mineral supply chain routes and deliver long-overdue economic returns. Success would depend on avoiding the familiar pitfalls that derailed earlier ventures such as the Saindak copper mine, developed in the 1990s with Chinese financing, leased to the Metallurgical Corporation of China since 2002, and still criticised for opaque revenue-sharing and limited local benefit. The first Reko Diq agreement, signed in 2006 with Tethyan Copper Company, later cancelled in 2011, leading to a decade-long arbitration that cost Pakistan nearly six billion US dollars in settlement. Similar ambitions have faltered before, from unfulfilled memoranda of understanding on CPEC industrial zones and Gwadar’s refinery complex to failed revival plans for Pakistan Steel Mills and stalled Thar coal gasification projects. If those lessons are ignored, this partnership risks joining the long list of headline agreements that promised transformation but delivered little.

China’s Restricted Rare Earth Portfolio

China’s export control measures now cover twelve of the seventeen rare earth elements, targeting those with the highest strategic and industrial value, along with other critical minerals. These materials are essential to advanced manufacturing, defence systems, renewable energy technologies, and high-performance electronics. The following elements are currently subject to restriction under the October 2025 framework. Together, these elements represent the core of global rare earth demand.

Critical sectors affected

Meet the Critical Minerals team

Trusted advice from a dedicated team of experts.

Henk de Hoop

Chief Executive Officer

Beresford Clarke

Managing Director: Technical & Research

Jamie Underwood

Principal Consultant

Dr Jenny Watts

Critical Minerals Technologies Expert

Ismet Soyocak

ESG & Critical Minerals Lead

Thomas Shann Mills

Senior Machine Learning Engineer

Rj Coetzee

Senior Market Analyst: Battery Materials and Technologies

Franklin Avery

Commodity Analyst

Brought to you by

Jamie Underwood

Principal Consultant

How can we help you?

SFA (Oxford) provides bespoke, independent intelligence on the strategic metal markets, specifically tailored to your needs. To find out more about what we can offer you, please contact us.