China’s Latest Rare Earth Export Controls

Critical minerals, policy, and the energy transition

10 October 2025

China’s REE Impact on Global Supply Chains and Industry

Strategic leverage, global disruption, and the Western response

China has taken a decisive step to consolidate control over critical materials by introducing sweeping new export controls on rare earth elements and associated technologies. Announced by the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) on 9 October 2025, these measures represent the most extensive tightening of China’s rare earth regulatory framework to date. Their timing, one day before President Donald Trump canceled his planned meeting with President Xi Jinping at the APEC summit in South Korea, signals a deliberate act of strategic escalation.

The legislation marks a major escalation in the global contest for industrial sovereignty. It carries significant implications for technology, defence, and manufacturing supply chains, positioning China as the world’s dominant producer and the regulator and gatekeeper of materials essential to advanced industry. By weaponising its control over extraction, processing, and magnet production, Beijing is transforming rare earths from an economic asset into an instrument of geopolitical leverage.

To implement the new framework, MOFCOM has issued a coordinated series of Announcements Nos. 55 through 62, each addressing a specific stage of the rare earth value chain. Collectively, these directives define the materials, technologies, and equipment now subject to control and establish new mechanisms for licensing, traceability, and compliance. The result is a comprehensive system governing the export of physical resources and the transfer of technical expertise, converting strategic intent into enforceable law.

Governments, corporations, and investors are now assessing the scale of disruption, warning of deepening strategic vulnerability across critical industries. The United States has described the legislation as a direct challenge to global technological stability, and allied economies are developing strategies for resilience focused on diversification of supply, industrial redundancy, and secure access to critical materials. For the West, this is no longer about competition but survival, requiring immediate action to rebuild industrial capacity, strengthen value chains, and secure strategic autonomy.

U.S. retaliatory measures: Escalation and economic fallout

In a direct response to China’s new export controls on rare earth materials, President Donald Trump announced on 10 October 2025 an unprecedented escalation in U.S. trade measures. The United States will impose an additional 100% tariff on all Chinese goods effective 1 November 2025, on top of existing 30% tariffs, bringing the total tariff burden to approximately 130%.

In a Truth Social statement, the President framed the move as a "defensive act of economic sovereignty," declaring that the United States "will no longer tolerate the weaponization of global supply chains." The announcement also included export controls on all "critical software", extending Washington’s technological confrontation with Beijing beyond hardware and materials.

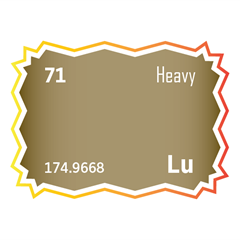

The new tariffs mark a dramatic reversal from the May 2025 U.S.-China de-escalation agreement, which had temporarily reduced tariffs to stabilise markets ahead of the APEC summit. That accord now lies in tatters, following China’s expanded rare earth export restrictions announced on 9 October 2025. The new measures added five more elements (samarium, gadolinium, lutetium, europium, and ytterbium) to its controlled list and imposed new "foreign direct product" rules.

Enforcement and global impact

China is constructing an extensive enforcement system to ensure transparency and compliance throughout global supply chains. This framework imposes new obligations on exporters and downstream users and marks a significant evolution in how Beijing tracks and regulates strategic materials. Key elements include:

-

Compliance notice regime: Exporters must disclose detailed information on the origin, composition, and transfer of all controlled materials. This establishes a traceable chain of custody for Chinese-origin rare earths and allows regulators to verify compliance at every stage of production and trade.

-

Non-automatic licensing system: Rather than imposing outright bans, MOFCOM will approve exports on a case-by-case basis. This enables Beijing to adjust market access according to political, economic, or diplomatic priorities, while maintaining exemptions for humanitarian, medical, or cooperative purposes.

-

Strategic leverage: This flexibility allows China to reward compliant partners and restrict those pursuing adversarial policies, transforming export control into an active instrument of geopolitical influence.

The consequences extend far beyond trade. These measures are a deliberate assertion of technological sovereignty, reshaping the global balance of industrial dependency. The impact will be most visible in the defence, semiconductor, renewable energy, and automotive sectors, where rare earths underpin key production capabilities.

China’s dominance in the rare earth market gives it unrivalled leverage over global supply and pricing. With most mining, processing, and magnet manufacturing capacity located within its territory, Beijing’s policy decisions can have immediate and global consequences. The new framework strengthens this dominance, cementing China’s position as the indispensable hub of the advanced materials supply chain.

The introduction of new compliance and licensing requirements is expected to create short-term bottlenecks and supply disruptions, particularly affecting manufacturers in the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Europe. Companies are likely to face increased costs, operational delays, and regulatory uncertainty as they adapt to the new controls. It will take years for Western nations to build the refining and magnet production capacity necessary to reduce dependence on Chinese supply meaningfully.

Beyond economics, the legislation functions as a strategic instrument of state policy, enabling China to respond to foreign technology restrictions, protect its domestic innovation base, and project influence across the global industrial ecosystem. By tightening control over rare earths, Beijing is both defending its industrial interests and reshaping the distribution of technological power. Rare earth policy now operates as an integrated component of China’s broader economic, diplomatic, and national security strategy.

China expands export controls across critical materials and advanced manufacturing

The scope of the new controls now extends well beyond rare earth elements, encompassing multiple categories of critical materials central to global industry, advanced manufacturing, and the clean energy transition.

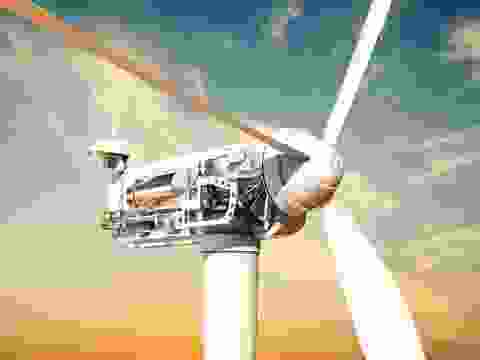

China has widened existing export restrictions on graphite to include synthetic graphite materials, effective 8 November 2025. The measures cover artificial graphite anode materials used in lithium-ion batteries, mixtures with natural graphite, and the equipment and processes required for their production. These controls directly target electric vehicle and energy storage supply chains, where Chinese producers already dominate global anode material capacity, tightening Beijing’s leverage over the global clean energy transition.

MOFCOM has introduced new export permit requirements for high-performance lithium-ion batteries with gravimetric energy density above 300 Wh/kg, as well as for cathode materials, precursors, and related manufacturing equipment. By restricting the transfer of advanced battery technology abroad, these measures constrain the localisation of next-generation energy storage production in the United States, Japan, and Europe, slowing Western efforts to develop self-sufficient battery supply chains.

The new framework extends to superhard materials, including diamond powders, single crystals, wire saws, grinding wheels, and chemical vapour deposition (CVD) equipment used in industrial diamond production. While jewellery-grade cultured diamonds are excluded, all technical-grade materials used in aerospace, semiconductor fabrication, and precision engineering are now restricted, adding further constraints to industries dependent on high-performance cutting and polishing technologies.

China has also expanded controls to include strategic metals vital to semiconductor, defence, and clean energy sectors, such as gallium, germanium, and antimony. Earlier in 2025, tungsten, indium, bismuth, tellurium, and molybdenum were added to the export control list, extending Beijing’s regulatory reach across materials essential for high-performance alloys, chip production, and renewable energy systems. These metals underpin precision manufacturing and weapons production, amplifying China’s leverage across critical Western industries.

Controls have additionally been extended to high-purity silicon and photovoltaic technologies. While industrial-grade silicon remains exportable, the new rules restrict semiconductor- and solar-grade polysilicon (6N–9N purity) and the technologies used in its manufacture. Exporters must now obtain government permits for the transfer of crystal-growth machinery, CVD systems, and process data related to silicon wafer fabrication. These restrictions target both semiconductor manufacturing and solar panel production, reinforcing China’s dominance in photovoltaic technology and chip-grade material supply.

Beyond raw materials, the export control framework now encompasses downstream manufacturing technologies, equipment, and chemical processes used in refining, magnet production, and battery assembly. Export licence applications from defence contractors, semiconductor producers, and high-technology firms are expected to face delays or denials, introducing new friction into global production networks and heightening uncertainty surrounding supply chain security for critical industries.

Four key components of China's new framework

China’s rare earth export control framework redefines its position as both the world’s dominant supplier and the principal regulator of critical materials. The framework extends beyond individual elements to encompass associated technologies, production systems, and intellectual property, allowing Beijing to assert control over every stage of the rare earth value chain, from extraction and separation to advanced magnet and component manufacturing.

These measures will directly affect defence, semiconductor, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing sectors across the United States, Europe, Japan, South Korea, and other allied economies. Companies dependent on Chinese-origin rare earths for magnets, sensors, batteries, and precision components now face heightened regulatory exposure, supply instability, and increased operational costs. The impact will cascade through global industries and ultimately reach consumers, raising prices for electric vehicles, electronics, and clean energy technologies, while slowing the pace of the global energy transition and digital innovation.

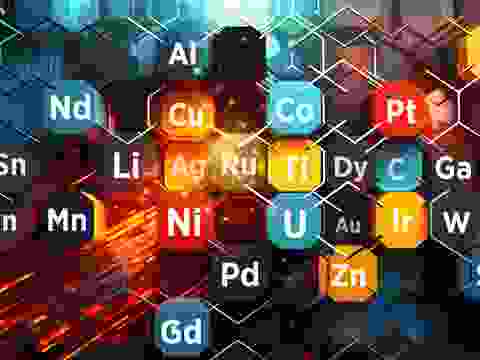

1) Expanded Element Control List

The expansion of the controlled element list represents a major escalation in China’s management of strategic resources. By adding five new rare earth elements to its restrictions, Beijing now holds direct regulatory control over the majority of globally significant inputs. This move tightens China’s hold on global supply chains and intensifies uncertainty across sectors including semiconductors, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing.

Newly restricted elements (effective 8 November 2025):

-

Holmium (Ho): Used in magnets, semiconductors, laser surgical instruments, and nuclear reactor control rods.

-

Erbium (Er): Essential for fibre-optic telecommunications and infrared technology.

-

Thulium (Tm): Applied in X-ray equipment, lasers, and ceramic materials for microwave devices.

-

Europium (Eu): Crucial for phosphors in LED lighting and display screens.

-

Ytterbium (Yb): Used in lasers and high-performance alloys.

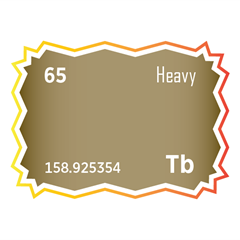

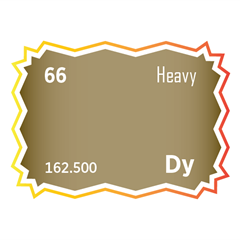

Previously restricted (since April 2025): Samarium, Gadolinium, Terbium, Dysprosium, Lutetium, Scandium, and Yttrium.

These measures demonstrate China’s determination to retain control over materials critical to the global energy transition and digital infrastructure. For Western economies seeking to decarbonise and reduce technological dependence, the expansion represents both a strategic challenge and a pressing incentive to diversify supply sources.

2) Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) Implementation

MOFCOM Announcement No. 61 introduces a Chinese version of the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR), extending Beijing’s jurisdiction to foreign companies whose products use Chinese-origin rare earth materials or technologies. This measure significantly broadens the reach of China’s export control authority.

Export licences are now required for:

-

Products containing 0.1% or more (by value) of Chinese-origin rare earths.

-

Items manufactured using Chinese rare earth technologies, regardless of production location.

-

Magnets or sputtering target materials derived from Chinese rare earth inputs.

This marks a fundamental shift in global trade governance, embedding Chinese regulatory power into international supply chains and allowing Beijing to influence how strategic materials are sourced, processed, and applied in advanced technologies.

3) Technology Export Controls

The tightening of technology export rules reflects China’s intent to protect industrial expertise and preserve its advantage in materials science and engineering. By restricting the transfer of technical data, designs, and manufacturing methods, Beijing seeks to prevent the diffusion of rare earth processing knowledge abroad.

Under MOFCOM Announcement No. 62, export restrictions now apply to:

-

Mining, smelting, and separation technologies for rare earth elements.

-

Magnetic material manufacturing techniques.

-

Recycling and recovery processes for secondary rare earth resources.

-

Production line design, maintenance, and upgrading technologies.

-

Technical data, including blueprints, process documentation, and simulation models.

These measures are designed to protect China’s industrial capability and ensure that advanced rare earth technologies remain under domestic control. In doing so, Beijing strengthens its position as the global leader in rare earth processing and magnet production.

4) Equipment and Materials Controls

Through MOFCOM Announcements 55 to 58, China has extended export restrictions to the machinery and materials essential for rare earth and battery production. These include:

-

Centrifugal extraction equipment.

-

Intelligent impurity removal systems.

-

Calcining kilns for rare earth production.

-

Superhard material processing systems.

-

Lithium battery and artificial graphite anode materials.

These measures broaden the scope of control beyond rare earths, linking the legislation to sectors central to electric vehicles, energy storage, and advanced manufacturing. The policy reinforces Beijing’s command over technologies critical to the energy transition and global industrial competitiveness.

Risks required to achieve Western rare earth resilience

Achieving long-term resilience in the Western rare earth supply chain will require not only coordination and investment, but a deliberate acceptance of strategic risk across economic, environmental, and geopolitical dimensions. The path to independence from Chinese dominance will involve immediate costs but deliver enduring security. Western nations must be prepared to bear short-term economic strain, environmental trade-offs, and political friction in pursuit of long-term sovereignty. The alternative, continued dependence on an adversarial supplier, poses far greater danger to defence readiness, industrial competitiveness, and geopolitical stability.

1. Economic and industrial risk

Rebuilding a rare earth supply chain from mine to magnet demands significant upfront investment in extraction, processing, and refining, typically at higher cost than Chinese production. Western governments will need to absorb near-term inefficiencies through subsidies, loan guarantees, and long-term procurement commitments. Accepting temporary market distortion and elevated input costs is the price of restoring secure access to strategic materials and achieving lasting autonomy.

2. Market and corporate risk

Governments must mobilise private industry to participate in a sector historically dominated by state-backed enterprises. This will expose firms to long-term market uncertainty, where returns rely on consistent policy, predictable demand, and allied coordination. Companies will need to invest ahead of profit, placing confidence in the durability of Western industrial strategy and the strength of public–private cooperation.

3. Environmental and regulatory risk

Rare earth mining and separation are chemically intensive processes with considerable environmental impact. Restoring domestic capacity will require governments to balance environmental integrity with strategic necessity, expediting approvals while maintaining public confidence. Controlled environmental trade-offs are unavoidable but manageable, provided they are accompanied by transparent oversight and a clear national security rationale.

4. Political and alliance management risk

A truly coordinated Western response depends on policy alignment across diverse national agendas, particularly between the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. Shared export controls, technology partnerships, and resource-sharing frameworks will require limited sovereignty concessions and political compromise among allies. Such integration is strategically essential but politically sensitive, especially where domestic industries compete for investment, employment, and market share.

5. Strategic and geopolitical risk

China is unlikely to remain passive. A decisive Western decoupling effort could trigger retaliatory export controls, price manipulation, or diplomatic pressure on resource-rich third countries. Western nations must be prepared for a period of strategic friction and supply volatility as Beijing moves to protect its market share and geopolitical leverage. The challenge is compounded by the fact that the West remains significantly behind in rare earth processing technology, engineering capability, and associated intellectual property. Closing this gap will require sustained innovation, research investment, and the rebuilding of technical expertise that has atrophied over decades of offshoring. Building resilience will require navigating inevitable confrontation, as the alternative is a sustained erosion of industrial capability and strategic autonomy.

Strategic Targeting and Restrictions

The legislation’s focus on the defence and semiconductor industries reflects its deliberate strategic purpose. China is not merely protecting its resources, it is shaping the structure of global technological power.

Defence Sector Prohibitions

By denying access to entities engaged in military or dual-use activities, Beijing is signalling its intent to prevent its resources from supporting adversarial defence programmes. Export licences will be denied for:

-

Foreign military users and defence contractors.

-

Subsidiaries and affiliates of defence-related enterprises.

-

Applications involving military or dual-use technologies.

-

Firms listed on China’s export control or watch lists.

These provisions align China’s export controls with national security priorities and restrict the flow of rare earths to defence supply chains viewed as contrary to its interests.

Semiconductor Industry Controls

Semiconductors form the foundation of modern technology and defence capability. China’s export controls now target the most advanced segments of this industry, with heightened scrutiny applied to:

-

Products used in 14-nanometre and more advanced logic chips.

-

256-layer and higher memory technologies.

-

Semiconductor manufacturing and testing equipment.

-

AI research with potential military or dual-use applications.

These controls limit access to high-end materials and equipment that could enhance foreign capabilities, while reinforcing China’s ambition for technological self-sufficiency in advanced chip production.

Operational measures: Contesting coercion and securing stockpiles

The confrontation between China and the West over control of critical materials has evolved into a prolonged contest of economic resilience and strategic endurance. China is now weaponising its dominance in rare earth extraction and processing to influence Western industrial and defence capability, testing the cohesion and preparedness of allied economies. In response, Western resilience must rest on more than investment and coordination; it requires a coherent framework of active measures designed to contest coercion, secure physical supply, and sustain production during crisis.

Governments and industry must act in concert to strengthen deterrence, expand redundancy, and ensure continuity of production across every critical supply chain. This demands a disciplined operational focus built around three mutually reinforcing priorities:

1. Contesting coercion and protecting supply lines to safeguard trade routes and resist economic pressure

-

Develop coordinated diplomatic and economic responses that unify allied reactions to export restrictions, price manipulation, or coercive trade practices. Rapid, collective countermeasures reduce vulnerability to economic fragmentation and demonstrate political solidarity.

-

Prepare reciprocal export controls and targeted trade measures to raise the cost of coercive behaviour, signalling that any attempt to weaponise supply chains will trigger proportional and sustained responses across allied markets.

-

Strengthen maritime and logistical security to protect critical shipments of rare earth materials and components. This includes enhanced naval coordination, secure convoy arrangements for high-value cargo, and the fortification of ports and transshipment hubs deemed essential to the rare earth supply chain.

-

Protect critical infrastructure and industrial logistics networks through upgraded physical and cyber defences, advanced cargo tracking, and enhanced counterintelligence cooperation between governments and major logistics operators.

-

Engage private-sector partners in supply chain protection through joint monitoring mechanisms, data-sharing agreements, and continuity planning for high-risk shipping routes and strategic inventories.

-

Maintain a unified communications doctrine to project allied resolve, deter opportunistic interference, and sustain confidence among industry and investors in the stability of critical material flows.

2. Building strategic stockpiles and inventory management systems, to guarantee access to critical materials under stress

-

Ensure priority allocation protocols to guarantee defence and critical infrastructure continuity during severe shortages, protecting national security and essential industrial operations.

-

Establish allied stockpiles of magnet-grade and separation-grade materials to provide emergency coverage for both military and civilian strategic sectors, ensuring the uninterrupted operation of high-value manufacturing during crises.

-

Coordinate with major industrial and defence contractors to create parallel corporate stockpiles that maintain production continuity under stress. Leading firms in aerospace, automotive, and technology manufacturing are already advancing this approach, securing long-term rare earth inventories to sustain business-as-usual operations during potential supply shocks.

-

Distribute both government and corporate reserves across secure, geographically diverse sites to reduce vulnerability and eliminate single points of failure. Strategic dispersion should extend across allied jurisdictions to guarantee access in times of regional disruption.

-

Introduce transparent governance frameworks with defined drawdown triggers, replenishment schedules, and audit requirements to ensure accountability and prevent distortion of commercial markets.

-

Finance and sustain stockpiles through public–private mechanisms, including long-term offtake agreements, pre-purchase contracts, and strategic investment guarantees that stabilise both government access and private-sector incentives to expand production capacity.

3. Expanding surge capacity, recycling, and demand management, to maintain industrial output and adapt to prolonged disruption

-

Expand modular and flexible processing capacity capable of rapid activation during crisis. Governments should fund and pre-certify “surge-ready” production lines for magnet manufacturing, separation, and refining to ensure industrial continuity during major supply disruptions. Allied nations must coordinate these facilities to form a distributed emergency network, ensuring output redundancy and mutual support.

-

Invest in large-scale recycling and urban mining infrastructure to recover rare earths from end-of-life electronics, vehicles, and industrial waste. Establish circular supply systems that can supply up to one-third of critical material demand during crisis conditions, reducing reliance on new extraction and imports.

-

Engage major manufacturers in pre-agreed surge production frameworks. Defence contractors, automotive firms, and clean energy producers should commit to standby production partnerships that enable the rapid scaling of essential component manufacturing when supply chains tighten. These industrial alliances form the operational backbone of Western supply resilience.

-

Implement coordinated demand-management frameworks to prioritise allocation between defence, energy, and industrial users during constrained supply. Predefined hierarchy systems should guarantee uninterrupted defence readiness while sustaining critical civilian infrastructure and energy security.

-

Support substitution research and material innovation through long-term funding for alternative magnetic alloys, ceramics, and advanced composites. Expanding viable substitutes for non-critical applications will ease strategic demand pressure and extend available reserves in future crises.

Conclusion: Strategic Implications for the UK, EU, and Allied Economies

China’s dominance in the rare earth sector defines the strategic environment of the decade ahead. Its control over extraction, processing, and advanced magnet production grants enduring leverage across global manufacturing, energy, and defence supply chains. This dominance enables Beijing to dictate access, shape pricing, and influence technological progress across every advanced economy. The rare earth export control regime is not a transient trade measure but a deliberate, long-term mechanism of geopolitical influence. It will take years for Western nations to build the refining and magnet production capacity necessary to meaningfully reduce dependence on Chinese supply.

For the United States and allied economies, these developments represent both a strategic warning and a call to sustained industrial mobilisation. The United States remains acutely exposed across its defence and aerospace sectors, where rare earths are indispensable for propulsion systems, precision-guided munitions, radar, and secure communications. This dependency constitutes a systemic vulnerability that extends across NATO and partner nations.

In the short term, these restrictions will likely slow the pace of U.S. defence production expansion, particularly in areas such as advanced munitions, missile guidance systems, and electronic warfare platforms. While the United States possesses the industrial base and capital to recover, the time required to localise the full rare earth supply chain will constrain output growth and complicate efforts to sustain high-volume defence manufacturing. This delay reinforces the urgency of building secure, allied-controlled material pipelines to underpin military readiness and deterrence.

Washington has begun to respond with renewed strategic focus. The U.S. Department of Defense has invested directly in the domestic rare earth supply chain, funding projects to establish a comprehensive “mine-to-magnet” capability and reduce reliance on Chinese processing. The Department has committed $400 million in equity investment to MP Materials, becoming the company’s largest shareholder, and provided an additional $150 million loan to expand domestic separation and refining capacity. These investments underpin the construction of MP Materials’ magnet manufacturing facility in Texas, part of a broader federal effort to re-establish end-to-end U.S. production capability.

In parallel, Apple has entered into a $500 million partnership with MP Materials to purchase U.S.-made magnets from recycled feedstock and co-develop a domestic recycling and processing facility. This alignment between corporate and national objectives reinforces the industrial shift toward strategic self-reliance. The acquisition of Less Common Metals by USA Rare Earth further strengthens allied control over magnet precursor and alloy production, expanding the Western capability base and deepening industrial resilience.

Recycling and closed-loop recovery programs are now emerging as central pillars of Western resilience. The United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union are funding large-scale initiatives to reclaim rare earths and battery materials from end-of-life electronics, vehicles, and industrial waste. At the same time, allied governments and investors are pursuing new mining and refining opportunities across North America, Australia, Europe, and emerging sites in Greenland, seeking to establish secure, Western-controlled supply chains for rare earth elements. Greenland’s deposits, alongside new research into recovering REEs from coal and coal by-products, represent promising alternative feed sources that could reduce dependence on Chinese supply. However, realising this potential will require substantial investment, environmental safeguards, and sustained political coordination to ensure these new resources translate into resilient industrial capacity.

The Western response must now be deliberate, coordinated, and sustained, driven by continued investment in domestic mining and refining, joint ventures with trusted partners, harmonised export controls, and shared allied infrastructure. Long-term resilience depends on an integrated industrial policy that unites public funding, private innovation, and alliance-based planning. Control over rare earth supply will define the extent of Western geopolitical power and its capacity to preserve technological and economic sovereignty.

Beyond defence and aerospace, the risks now extend across the industrial economy. The automotive, renewable energy, and electronics sectors are competing directly with defence for limited rare earth resources. Electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators, and high-performance batteries all depend on rare earth magnets and alloys. Supply disruption would raise production costs, delay clean energy deployment, and constrain the expansion of strategic manufacturing bases across North America and Europe. Such pressures will slow industrial growth, undermine investment confidence, and make energy transition resilience harder to achieve across the Western world.

For the European Union, the legislation reinforces the urgency of executing the Critical Raw Materials Act with precision and speed. The EU must convert its strategic intent into operational capability, developing extraction, refining, and recycling capacity within Europe and through partnerships with democratic producers. Member states must cooperate to ensure scale and consistency, supported by investment incentives, technology exchange, and cross-border projects. Europe’s ability to deliver its energy transition and maintain industrial competitiveness depends on achieving strategic independence from Chinese control.

For the United Kingdom, the new export regime exposes a structural weakness in access to critical materials vital to defence, energy security, and advanced manufacturing. Reliance on Chinese-processed inputs leaves key sectors vulnerable to coercion and disruption. The UK must respond decisively: build domestic refining capacity, establish strategic reserves, integrate into allied supply chains, and align policy with the United States, Canada, and Australia. Rare earth security must be treated as a core national security issue, embedded within defence, industrial, and energy strategy.

These developments unfold against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, which has fundamentally altered the global security landscape and redefined the contest between democratic and authoritarian powers. Russia’s sustained aggression has deepened its economic and technological dependence on China, entrenching a Beijing–Moscow axis that spans resources, energy, and military technology. By tightening control over rare earths, China strengthens its bargaining position with Russia and signals its willingness to leverage industrial supply chains as tools of geopolitical coercion. This alignment increases strategic pressure on NATO and its partners, reinforcing the need for collective resource resilience alongside military support for Ukraine.

Strategic foresight and unity of purpose are now imperative. The United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and allied partners must treat rare earth security as a shared mission of industrial defence. This is not a commercial adjustment but a test of long-term sovereignty and strategic endurance. Sustained investment, coordinated technology programmes, surge capacity planning, and coherent political leadership are required to rebuild resilience and rebalance the global system. The objective is clear: to ensure that access to critical materials remains secure, affordable, and aligned with democratic interests, and that the free world retains the industrial and strategic strength to defend them.

TRANSLATED MOFCOM ANNOUNCEMENTS

Announcement No. 55

The Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Customs Announcement No. 55 of 2025 announced the decision to implement export controls on superhard materials-related items

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau Announcement No. 55 of 2025 of the General Administration of Customs of the Ministry of Commerce Date of Issue: October 09, 2025

In accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China, the Foreign Trade Law of the People's Republic of China, the Customs Law of the People's Republic of China, and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on Export Control of Dual-Use Items, to safeguard national security and interests, and to fulfill international obligations such as non-proliferation, with the approval of the State Council, it is decided to implement export controls on the following items:

-

2C902.a. Artificial diamond powder with an average particle size of less than or equal to 50 μm (reference tariff number: 71051020)

-

2C902.b. Artificial diamond single crystal with an average particle size greater than 50 μm and less than or equal to 500 μm (reference tariff number: 71051020) Note: Subparagraph 2C902.b does not regulate lab-grown diamonds used in decoration and jewellery.

-

2C902.c. Artificial diamond wire saw with all the following characteristics:

-

-

Wire diameter less than or equal to 45 μm;

-

The average particle size of the diamond contained is less than or equal to 8 μm;

-

The breaking tensile force is less than or equal to 16 N.

-

2C902.d. Artificial diamond grinding wheel with all of the following characteristics (reference tariff number: 68042110):

-

-

-

-

1. The hardness of diamond teeth is less than or equal to 30 HRB;

-

2. The average particle size of the diamond contained is less than or equal to 5 μm;

-

3. The maximum working speed is greater than or equal to 40 m/s.

-

5. 2B005.b. DC arc plasma jet chemical vapor deposition (DCPCVD) equipment (reference tariff number: 84798999).

-

6. 2E902 DC arc plasma jet chemical vapour deposition (DCPCVD) process technology.

-

-

Export operators exporting the above items shall apply for permission from the competent department of commerce under the State Council in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items.

Export operators shall be responsible for the authenticity of the customs declared goods, strengthen the identification of export items, and if they are controlled items, they must indicate "dual-use items" and list the export control code of dual-use items in the remarks column of the customs declaration form; If it is not a controlled item but the parameters, indicators, performance, etc. are close, it must indicate "not a controlled item" in the remarks column of the customs declaration form and fill in the specific parameters and indicators. If there is any doubt about the completeness, accuracy and authenticity of the above-mentioned information, the customs will question it in accordance with the law, and the export goods will not be released during the questioning period.

This announcement will be officially implemented on November 8, 2025. The "Export Control List of Dual-Use Items of the People's Republic of China" will be updated simultaneously.

Announcement No. 56

The Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Customs Announcement No. 56 of 2025 announced the decision to implement export controls on some rare earth equipment and raw materials related items

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau Announcement No. 56 of 2025 of the General Administration of Customs of the Ministry of Commerce Date of Issue: October 09, 2025

In accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China, the Foreign Trade Law of the People's Republic of China, the Customs Law of the People's Republic of China, and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on Export Control of Dual-Use Items, in order to safeguard national security and interests, and to fulfill international obligations such as non-proliferation, with the approval of the State Council, it is decided to implement export controls on the following items:

1. 2B902 Rare earth production and processing equipment

(1) 2B902.a. Centrifugal extraction equipment for rare earth production and processing.

(2) 2B902.b. Ionic rare earth ore intelligent continuous impurity removal and precipitation equipment with a daily leachable volume greater than or equal to 5000 m³.

(3) 2B902.c. Rare earth roasting kiln with all the following characteristics:

-

-

Size range: Φ1.8×20 m~Φ4.6×80 m;

-

Masonry lining materials in the kiln cylinder, including graphite bricks, high alumina bricks, mullite bricks and other materials resistant to concentrated sulfuric acid, hydrofluoric acid corrosion and temperature;

-

The reaction temperature is less than or equal to 850 °C.

-

(4) 2B902.d. Extraction tank with a mixing chamber volume of 0.5~14.2m³ for rare earth separation and purification.

(5) 2B902.e. Ion adsorption equipment for rare earth separation and purification.

(6) 2B902.f. Rare earth reaction tank with a volume of 10~50 m³ for precipitation and crystallization of the reaction tank.

(7) 2B902.g. Parts used for items controlled by 2B902.f:

-

-

Sedimentation crystallisation agitator (reference tariff number: 84798999);

-

Mixer paddle (reference tariff number: 84799090);

-

Motor with output power of 5.5~37 kW.

-

(8) 2B902.h. Resistance furnace for rare earths with all the following characteristics (refer to the tariff number: 85141990):

-

-

Reaction temperature 320~650 °C;

-

The parts are made of manganese steel, nickel-chromium alloy steel and other corrosion-resistant materials.

-

(9) 2B902.i. Any of the following equipment for rare earth metal electrolysis:

-

-

Electrolytic rectification equipment;

-

Feeding equipment;

-

Rare earth metal siphon furnace system;

-

Exhaust gas treatment equipment.

-

(10) 2B902.j. Rare earth electrolyser with all the following characteristics (reference tariff number: 85433000):

-

-

The cell type is a refractory brick-lined cell;

-

The anode is made of graphite material;

-

The cathode is made of tungsten material;

-

Current range: 6,000–30,000 A;

-

Anode current density range: 5–7 A/cm²;

-

Cathode current density range: 1–2 A/cm².

-

(11) 2B902.k. Vacuum Induction Reduction Furnace with all of the following characteristics:

-

-

Intermediate-frequency power supply frequency: 1–8 kHz;

-

Heating temperature: 0–1700 °C;

-

Vacuum degree ≥ 1×10⁻³ Pa;

-

Melting capacity: 10–300 kg.

-

(12) 2B902.l. Vacuum Carbon Tube Furnace with all of the following characteristics:

-

-

Heating temperature: 0–1700 °C;

-

Vacuum degree ≥ 1×10⁻³ Pa;

-

Melting capacity: 10–300 kg.

-

(13) 2B902.m. Czochralski Method Rare Earth Crystal Growth Furnace

with all of the following characteristics (reference tariff number: 85142000):

-

-

Heating method: induction heating;

-

Maximum heating temperature ≥ 2300 °C;

-

Equipped with automatic constant-diameter crystal growth control function.

-

(14) 2B902.n. Crucible-Down Method Rare Earth Crystal Growth Furnace

with all of the following characteristics (reference tariff number: 85141990):

-

-

Heating method: resistance heating;

-

Maximum heating temperature ≥ 1400 °C.

-

It has multi-temperature zone heating function.

-

(15) 2B902.o. Rare earth permanent magnet vacuum induction casting furnace:

-

-

Periodic vacuum induction casting furnace (reference tariff number: 85142000);

-

Induction heating vacuum melting furnace.

-

(16) Parts used in 2B902.p. for items controlled by 2B902.o:

-

-

Water-cooled cable;

-

Copper rollers;

-

Crucible;

-

Inclination controller;

-

Cooling system.

-

(17) 2B902.q. Rare earth permanent magnet hydrogen crushing furnace:

-

-

Continuous atmosphere heat treatment furnace;

-

Rotary hydrogen crushing furnace;

-

Explosion-proof continuous hydrogen crushing furnace.

-

(18) Parts used in 2B902.r. for items controlled by item 2B902.q:

-

-

Valves;

-

Hydrogen busbar.

-

(19) 2B902.s. Air flow mill for rare earth permanent magnets with all the following characteristics:

-

-

Particle size less than or equal to 5μm;

-

The total powder yield is greater than or equal to 99%;

-

The oxygen content inside the system is less than or equal to 80ppm.

-

(20) 2B902.t. Rare earth permanent magnet forming press with magnetic field with magnetic induction strength greater than or equal to 1.5T.

(21) 2B902.u. Automatic hot pressing equipment for rare earth permanent magnets.

(22) 2B902.v. cold isostatic press for rare earth permanent magnets not controlled by 2B104 (reference tariff number: 84798310).

(23) 2B902.w. Any of the following rare earth permanent magnet vacuum sintering furnaces with a cooling time of less than or equal to 20 min, a heating temperature of 500~1200 °C, and a temperature uniformity of ±3 °C at 1000 °C:

-

-

Single horizontal sintering furnace;

-

Continuous vacuum sintering furnace;

-

Vertical sintering furnace.

-

(24) 2B902.x. Equipment for rare earth magnetic material processing:

-

-

Multi-wire cutting machine;

-

Laser cutting equipment;

-

Automatic gluing machine;

-

Vertical grinding;

-

Double-sided mill;

-

Face milling;

-

Pass-through grinder.

-

(25) 2B902.y. Grain boundary diffusion equipment:

-

-

Physical vapor deposition magnetron sputtering coating equipment (reference tariff number: 84798999);

-

Rare earth permanent magnet vacuum diffusion furnace;

-

Screen printing device for rare earth permanent magnets.

-

(26) 2B902.z. Vertical kilns with a size range greater than or equal to Φ19×21 m for the recycling of rare earth secondary resources.

2. 1C914 rare earth raw materials related items

(1) 1C914.a. Rare earth ore (reference tariff number: 25309020):

-

-

Fluorocerium ore;

-

Monazite;

-

Ion-adsorbed rare earth ore.

-

(2) 1C914.b. Rare earth ore flotation agent containing hydroxyxamic acid or phosphate ester collectors.

(3) 1C914.c. Extractants for rare earth production:

-

P507:2-ethylhexylphosphonic acid mono2-ethylhexyl ester (CAS 14802-03-0) (reference tariff number: 29319000);

-

P204: Dis(2-ethylhexyl)phosphate (CAS 298-07-7) (reference tariff number: 29199000);

-

Naphthenic acid (CAS 1338-24-5) (reference tariff number: 38249999);

-

N235: Trioctanyl tertiary amines (CAS 68814-95-9) (reference tariff number: 38249999);

-

C272: bis(2,4,4-trimethylpentyl)phosphonic acid (CAS 83411-71-6).

Export operators exporting the above items shall apply for permission from the competent department of commerce under the State Council in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items.

Export operators shall be responsible for the authenticity of the customs declared goods, strengthen the identification of export items, and if they are controlled items, they must indicate "dual-use items" and list the export control code of dual-use items in the remarks column of the customs declaration form; If it is not a controlled item but the parameters, indicators, performance, etc. are close, it must indicate "not a controlled item" in the remarks column of the customs declaration form and fill in the specific parameters and indicators. If there is any doubt about the completeness, accuracy and authenticity of the above-mentioned information, the customs will question it in accordance with the law, and the export goods will not be released during the questioning period.

This announcement will be officially implemented on November 8, 2025. The "Export Control List of Dual-Use Items of the People's Republic of China" will be updated simultaneously.

Announcement No. 57

The Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Customs Announcement No. 57 of 2025 announced the decision to implement export controls on some medium and heavy rare earth-related items

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau Announcement No. 57 of 2025 of the General Administration of Customs of the Ministry of Commerce Date of Issue: October 09, 2025

In accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China, the Foreign Trade Law of the People's Republic of China, the Customs Law of the People's Republic of China, and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on Export Control of Dual-Use Items, in order to safeguard national security and interests, and to fulfill international obligations such as non-proliferation, with the approval of the State Council, it is decided to implement export controls on the following items:

1. 1C909 Holmium-related items

(1) 1C909.a. Holmium metal, holmium-containing alloys and related products:

1. Holmium metal (reference tariff number: 28053019).

2. Holmium-containing alloys:

-

- holmium-copper alloy;

- magnesium-holmium alloy;

- Holmium ferroalloy.

3. Holmium-containing targets:

-

- holmium target;

- Holmium-copper alloy targets.

4. Holmium-containing permanent magnet material.

5. Holmium-containing crystalline materials.

6. Holmium-containing magnetic refrigeration materials.

7. Magnetostrictive materials containing holmium.

(2) 1C909.b. holmium oxide and its mixtures.

(3) 1C909.c. holmium-containing compounds and their mixtures.

2. 1C910 Erbium-related items

(1) 1C910.a. Metallic erbium, erbium-containing alloys and related products:

1. Erbium metal (reference tariff number: 28053019).

2. Alloys containing erbium:

-

- Erbium-aluminum alloys;

- [Retention].

3. Erbium-containing targets:

-

- Erbium target;

- [Retention].

4. Erbium-containing crystalline materials.

5. Optical fiber material containing erbium.

6. Erbium-containing hydrogen storage materials.

7. Ceramic material containing erbium.

(2) 1C910.b. Erbium oxide and its mixtures.

(3) 1C910.c. Erbium-containing compounds and their mixtures.

3. 1C911 Thulium-related items

(1) 1C911.a. Thulium metal, alloys containing thulium and related products:

1. Thulium metal (reference tariff number: 28053019).

2. Thulium Containing Targets:

-

- Thulium targets;

- [Retention].

3. Crystalline materials containing thulium.

4. Luminescent materials containing thulium.

(2) 1C911.b. Thullium oxide and its mixtures.

(3) 1C911.c. Thulium-containing compounds and their mixtures.

4. 1C912 europium-related items

(1) 1C912.a. Metallic europium, alloys containing europium and related products:

1. Metal Europium (reference tariff number: 28053019).

2. Alloys containing europium:

a. Magnesium-europium alloys;

b. [Retention].

3. Europium-containing targets:

a. europium target;

b. [Retention].

4. Europium-containing luminous materials:

a. phosphor;

b. [Retention].

5. Crystalline materials containing europium.

6. Hydrogen-absorbing materials containing europium.

(2) 1C912.b. europium oxide and its mixtures.

(3) 1C912.c. Europium-containing compounds and their mixtures.

5. 1C913 Ytterbium-related items

(1) 1C913.a. Metal ytterbium, alloys containing ytterbium and related products:

1. Metal ytterbium (reference tariff number: 28053019).

2. Ytterbium-containing targets:

a. ytterbium target;

b. [Retention].

3. Crystalline materials containing ytterbium.

4. Fiber optic material containing ytterbium.

5. Thermal shielding coating material containing ytterbium.

(2) 1C913.b. Ytterbium oxide and its mixtures.

(3) 1C913.c. Ytterbium-containing compounds and their mixtures.

Illustrate:

-

The alloys controlled by 1C909.a.2, 1C910.a.2, and 1C912.a.2 include ingots, blocks, strips, wires, sheets, rods, plates, tubes, granules, powders, and other forms.

-

The targets controlled by 1C909.a.3, 1C910.a.3, 1C911.a.2, 1C912.a.3, and 1C913.a.2 include sheets, tubes and other forms.

-

Permanent magnet materials regulated by 1C909.a.4 include magnets or magnetic particles.

-

Oxides, compounds and their mixtures controlled by items 1C909, 1C910, 1C911, 1C912, and 1C913 include but are not limited to powders.

Export operators exporting the above items shall apply for permission from the competent department of commerce under the State Council in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items.

Export operators shall be responsible for the authenticity of the customs declared goods, strengthen the identification of export items, and if they are controlled items, they must indicate "dual-use items" and list the export control code of dual-use items in the remarks column of the customs declaration form; If it is not a controlled item but the parameters, indicators, performance, etc. are close, it must indicate "not a controlled item" in the remarks column of the customs declaration form and fill in the specific parameters and indicators. If there is any doubt about the completeness, accuracy and authenticity of the above-mentioned information, the customs will question it in accordance with the law, and the export goods will not be released during the questioning period.

This announcement will be officially implemented on November 8, 2025. The "Export Control List of Dual-Use Items of the People's Republic of China" will be updated simultaneously.

Announcement No. 58

The Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Customs Announcement No. 58 of 2025 announced the decision to implement export controls on items related to lithium batteries and artificial graphite anode materials

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau Announcement No. 58 of 2025 of the General Administration of Customs of the Ministry of Commerce Date of Issue: October 09, 2025

In accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China, the Foreign Trade Law of the People's Republic of China, the Customs Law of the People's Republic of China, and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on Export Control of Dual-Use Items, in order to safeguard national security and interests, and to fulfill international obligations such as non-proliferation, with the approval of the State Council, it is decided to implement export controls on the following items:

1. Lithium battery-related items

(1) 3A001 Rechargeable and dischargeable lithium-ion batteries (including cells and battery packs) with a weight energy density greater than or equal to 300 Wh/kg (reference tariff number: 85076000).

(2) 3B901.a. Equipment for manufacturing rechargeable and discharged lithium-ion batteries:

-

Winding machine (reference tariff number: 84798999);

-

Laminating machine (reference tariff number: 84798999);

-

Liquid injection machine (reference tariff number: 84798999);

-

Heat press;

-

Chemical component volume system;

-

Divider cabinet.

(3) 3E901.a. Technology used to produce the items controlled by 3A001.

2. Cathode material-related items

(1) 3C901.a.1. The compaction density is greater than or equal to 2.5 g/cm3and lithium iron phosphate cathode material with a capacity greater than or equal to 156 mAh/g (reference tariff number: 28429040).

(2) 3C901.a.2. Precursor-related items of ternary cathode materials:

-

-

Nickel-cobalt-manganese hydroxide (reference tariff number: 28539030);

-

Nickel-cobalt-aluminium hydroxide (reference tariff number: 28539050).

-

(3) 3C901.a.3. Lithium-rich manganese-based cathode materials.

(4) 3B901.b. Equipment for manufacturing cathode materials for rechargeable and discharged lithium-ion batteries:

-

-

Roller kiln;

-

High-speed mixer;

-

Sanding machine;

-

Airflow grinder.

-

3. Graphite anode material related items

(1) 3C901.b.1. Artificial graphite anode materials.

(2) 3C902.b.2. Anode materials mixed with artificial graphite and natural graphite.

(3) 3B901.c.1. Granulation process equipment for the production of graphite anode materials:

-

-

Granulation volume greater than or equal to 5 m3 vertical granulating kettle;

-

Granulation volume greater than or equal to 5 m3. The continuous granulation kettle.

-

(4) 3B901.c.2. Graphitisation equipment for the production of graphite anode materials:

-

-

Box furnace;

-

Acheson furnace;

-

Inner string furnace;

-

Continuous graphitisation furnace.

-

(5) 3B901.c.3. Coated modification equipment for the production of graphite anode materials:

-

-

Fusion coating equipment with a volume greater than 300 L;

-

Volume greater than 60 m3spray drying equipment;

-

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) rotary kilns with a barrel diameter greater than 0.5 m.

-

(6) 3E901.b. Process and technology for the production of graphite anode materials:

-

-

Granulation process;

-

Continuous graphitisation technology;

-

Liquid phase coating technology.

-

Export operators exporting the above items shall apply for permission from the competent department of commerce under the State Council in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items.

Export operators shall be responsible for the authenticity of the customs declared goods, strengthen the identification of export items, and if they are controlled items, they must indicate "dual-use items" and list the export control code of dual-use items in the remarks column of the customs declaration form; If it is not a controlled item but the parameters, indicators, performance, etc. are close, it must indicate "not a controlled item" in the remarks column of the customs declaration form and fill in the specific parameters and indicators. If there is any doubt about the completeness, accuracy and authenticity of the above-mentioned information, the customs will question it in accordance with the law, and the export goods will not be released during the questioning period.

This announcement will be officially implemented on November 8, 2025. The "Export Control List of Dual-Use Items of the People's Republic of China" will be updated simultaneously.

Announcement No. 61

Announcement No. 61 of 2025 of the Ministry of Commerce announced the decision to implement export controls on relevant rare earth items overseas

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau Announcement No. 61 of 2025 of the General Administration of Customs of the Ministry of Commerce Date of Issue: October 09, 2025

In order to safeguard national security and interests, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China, the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items, and other relevant laws and regulations, with the approval of the State Council of China, it has been decided to adopt the following export control measures:

1. Overseas organisations and individuals (hereinafter referred to as "overseas specific export operators") must obtain an export license for dual-use items issued by the Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China before exporting the following items to other countries and regions other than China:

(1) Containing, integrating or mixing the items listed in Part 1 of Annexe 1 of this Announcement originating in China manufactured overseas in Part 2 of Annexe 1, and the proportion of the items listed in Part 1 of Annex 1 to the value of the items listed in Part II of Annexe 1 manufactured overseas reaches 0.1% or more;

(2) The items listed in Annexe 1 of this announcement are produced overseas using technologies related to rare earth mining, smelting and separation, metal smelting, magnetic manufacturing, and rare earth secondary resource recycling originating in China;

(3) Items listed in Annexe 1 of this announcement originating in China.

2. In principle, export applications to overseas military users and to importers and end users (including subsidiaries, branches and other branches controlled by 50% or more of their control) listed on the export control list and watch list will not be permitted.

3. Export applications used or likely to be used for the following end-uses shall not be permitted in principle:

(1) Design, development, production and use of weapons of mass destruction and their means of delivery;

(2) Terrorist purposes;

(3) Military use or enhancement of military potential.

4. The export application for end-use is R&D and production of logic chips of 14nm and below or memory chips of 256 layers and above, as well as the production equipment, test equipment and materials for the manufacture of semiconductors in the above-mentioned processes, or the development of artificial intelligence with potential military uses, and is approved on a case-by-case basis.

5. For export applications for humanitarian relief such as emergency medical treatment, response to public health emergencies, and natural disaster relief, overseas export operators do not need to apply for an export license for dual-use items, but should report to the Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China by email (jingwaibaogao@mofcom.gov.cn) no later than 10 working days after export, and promise that the relevant items will not be used for purposes that endanger China's national security and interests.

6. Overseas specific export operators applying for dual-use export licenses shall submit relevant documents in accordance with Article 16 of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items and the requirements of the Dual-use Export Licensing Examination and Approval System of the Ministry of Commerce of China, and the relevant documents shall be in Chinese. The website of the approval system is: http://ecomp.mofcom.gov.cn.

Specific overseas export operators can directly submit application documents, or entrust enterprises, intermediary service agencies, chambers of commerce, associations, etc. located in China to handle the application. The relevant intermediary service institutions, chambers of commerce, or associations shall be independent legal persons or unincorporated organisations that can independently bear legal responsibilities.

If the specific overseas export operator cannot determine whether the items to be exported are items that should apply for an export license in accordance with the provisions of this announcement, they can consult by email (jingwaizixun@mofcom.gov.cn).

7. Domestic export operators exporting dual-use items listed in Part 1 of Annexe 1 of this announcement shall fill in the final destination country or region as required during export customs declaration, and issue a "Compliance Notice" to overseas importers and end users in accordance with the compliance guidelines attached to this announcement.

Overseas export operators shall issue a Compliance Notice to the next recipient when transferring or exporting items controlled by this Announcement in accordance with the requirements of the compliance guidelines attached to this announcement.

8. The "One (1)" and "One (2)" parts of this announcement will be implemented from December 1, 2025. Part "1 (3)" of this announcement shall be implemented from the date of promulgation.

Annex:

- Item list.wps

- Compliance Notice Guidelines.wps

Announcement No. 62

Announcement No. 62 of 2025 of the Ministry of Commerce announces the decision to implement export controls on rare earth-related technologies

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau Issued Number: Ministry of Commerce Announcement No. 62 of 2025

Date of Issue: October 09, 2025

In order to safeguard national security and interests, in accordance with the relevant provisions of laws and regulations such as the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China and the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items, with the approval of the State Council, it is decided to implement export controls on rare earth-related technologies and other items, and the relevant provisions are as follows:

1. The following items shall not be exported without permission:

(1) Technologies and carriers related to rare earth mining, smelting and separation, metal smelting, magnetic manufacturing, and recycling of rare earth secondary resources; (Regulatory Code: 1E902.a)

(2) Rare earth mining, smelting and separation, metal smelting, magnetic material manufacturing, rare earth secondary resource recycling related production line assembly, commissioning, maintenance, repair, upgrade and other technologies. (Regulatory Code: 1E902.b)

If the exporter knows that the export of uncontrolled goods, technologies or services is used or substantially contributes to overseas rare earth mining, smelting and separation, metal smelting, magnetic material manufacturing, and rare earth secondary resource recycling activities, it shall apply to the Ministry of Commerce for an export license for dual-use items before exporting in accordance with Article 12 of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China and Article 14 of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items. It may not be provided without permission.

The meaning and scope of "rare earth", "smelting and separation", "metal smelting" and "rare earth secondary resources" in this announcement shall be implemented in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Administration of Rare Earths. The "magnetic material manufacturing" technology in this announcement refers to the manufacturing technology of samarium cobalt, neodymium iron boron, and cerium magnets. The technologies and their carriers mentioned in this announcement include technology-related data and other data, such as design drawings, process specifications, process parameters, processing procedures, simulation data, etc.

2. The export operators referred to in this announcement include Chinese citizens, legal persons and unincorporated organisations, as well as all natural persons, legal persons and unincorporated organisations in China.

The term "export" as used in this announcement refers to the transfer of controlled items listed in this announcement from the territory of the People's Republic of China to overseas, or the provision of domestic or foreign products to foreign organisations or individuals, including trade exports, as well as transfer or provision through intellectual property licensing, investment, exchange, gift, exhibition, display, testing, testing, assistance, teaching, joint research and development, employment or employment, consulting, etc.

3. Export operators shall apply for an export license from the Ministry of Commerce in accordance with Article 16 of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items; If applying for export technology, the export operator shall submit the "Explanation of the Transfer or Provision of Export Controlled Technology" at the same time in accordance with the requirements of Annex 1; If the technology controlled by this announcement is provided to an overseas organisation or individual located in the territory of the People's Republic of China, the "Explanation on the Provision of Export Control Technology in Domestic Territory" shall be submitted at the same time in accordance with the requirements of Annex 2.

Export operators shall use the license in accordance with Article 18 of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on the Export Control of Dual-Use Items and perform their reporting obligations in accordance with the requirements of the license.

4. Export operators should strengthen their compliance awareness, understand the performance indicators and main uses of the goods, technologies and services to be exported, and determine whether they are dual-use items. If it is impossible to determine whether the items to be transferred or provided are subject to the control of this announcement, or whether the relevant situation is subject to the control of this announcement, you may consult the Ministry of Commerce.

5. No unit or individual shall provide intermediary, matchmaking, agency, freight, delivery, customs declaration, third-party e-commerce trading platform and financial services for violations of this announcement. If it may involve the export of items controlled by this announcement, the service provider shall take the initiative to ask the service recipient whether the export activities are subject to the jurisdiction of this announcement and whether they are applying for an export license or obtaining a license. Export operators who have obtained export licenses for dual-use items shall take the initiative to present the license documents to the relevant service providers.

6. Technologies that have entered the public domain, technologies in basic scientific research, or technologies necessary for ordinary patent applications are not subject to the jurisdiction of this announcement. From the effective date of this announcement, the technology that has not entered the public domain controlled by this announcement shall be punished in accordance with Article 34 of the Export Control Law of the People's Republic of China if it is disclosed to unspecified objects without permission.

7. Chinese citizens, legal persons and unincorporated organisations shall not provide any substantive assistance and support for overseas rare earth mining, smelting and separation, metal smelting, magnetic material manufacturing, and rare earth secondary resource recycling activities without permission.

8. This announcement shall be implemented from the date of promulgation. The "Export Control List of Dual-Use Items of the People's Republic of China" will be updated simultaneously.

Annex:

1. Guidelines for filling in the "Instructions on Transferring or Providing Export Control Technology".wps

2. "Instructions on the Provision of Export Control Technologies in China" Filling Guide.wps

Anti-drone Technologies

Announcement on the Working Mechanism of the Unreliable Entity List on the inclusion of foreign entities such as anti-drone technology companies in the list of unreliable entities

Issued by: Security and Control Bureau

Working mechanism of the list of unreliable entities [2025] No. 10 issued on October 09, 2025

In order to safeguard national sovereignty, security and development interests, in accordance with the Foreign Trade Law of the People's Republic of China, the National Security Law of the People's Republic of China, the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law of the People's Republic of China and other relevant laws, the working mechanism of the Unreliable Entity List decides to include foreign entities such as anti-drone technology companies, TechInsights and their branches in the list of unreliable entities in accordance with Articles 2, 8 and 10 of the Provisions on the List of Unreliable Entities, and takes the following measures:

-

Prohibit the above-mentioned entities from engaging in import and export activities related to China;

-

Prohibit the above-mentioned entities from making new investments in China;

-

It is prohibited for organisations and individuals in China to conduct related transactions, cooperation, and other activities with the above-mentioned entities, especially to transmit data and provide sensitive information to the above-mentioned entities.

Matters not covered in this announcement shall be implemented in accordance with the "Provisions on the List of Unreliable Entities".

This announcement shall be implemented from the date of promulgation.

Foreign entities on the Unreliable Entity List

-

Dedrone by Axon

-

DZYNE Technologies

-

Elbit Systems of America, LLC

-

Epirus, Inc.

-

AeroVironment, Inc.

-

Exelis Inc.

-

Alliant Techsystems Operations LLC

-

BAE Systems, Inc.

-

Teledyne FLIR, LLC

-

VSE Corporation

-

Cubic Global Defense

-

Recorded Future, Inc.

-

Halifax International Security Forum

- TechInsights Inc. and its affiliates

-

- -TechInsights Inc.

- -TechInsights Europe Limited

- -TechInsights Europe Sp zo.o

- -TechInsights Japan KK

- -TechInsights USA Inc

- -TechInsights Korea Co. Ltd.

- -TechInsights Market Analysis Limited

- -SARL Strategy Analytics

- -Strategy Analytics GmbH Market Research and Management Consulting

- -SARI Strategy Analytics Private Limited

China’s Restricted Rare Earth Portfolio

China’s export control measures now cover twelve of the seventeen rare earth elements, targeting those with the highest strategic and industrial value. These materials are essential to advanced manufacturing, defence systems, renewable energy technologies, and high-performance electronics. The following elements are currently subject to restriction under the October 2025 framework. Together, these elements represent the core of global rare earth demand.

Critical sectors affected

Meet the Critical Minerals team

Trusted advice from a dedicated team of experts.

Henk de Hoop

Chief Executive Officer

Beresford Clarke

Managing Director: Technical & Research

Jamie Underwood

Principal Consultant

Dr Jenny Watts

Critical Minerals Technologies Expert

Ismet Soyocak

ESG & Critical Minerals Lead

Thomas Shann Mills

Senior Machine Learning Engineer

Rj Coetzee

Senior Market Analyst: Battery Materials and Technologies

Franklin Avery

Commodity Analyst

Brought to you by

Jamie Underwood

Principal Consultant

How can we help you?

SFA (Oxford) provides bespoke, independent intelligence on the strategic metal markets, specifically tailored to your needs. To find out more about what we can offer you, please contact us.